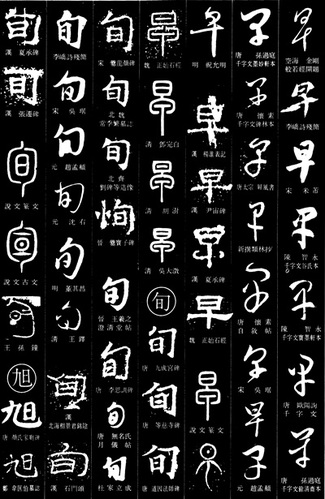

Chinese writing is the oldest writing system on our planet. It precedes Sumerian cuneiform by at least some 1500 years, going all the way back to the Yangshao culture (仰韶文化; 5000 – 2000 B.C.E.). It is also the most advanced writing system that human race managed to develop. We know for a fact that the total number of Chinese characters exceeds 90,000. If one compares this against the 23 letters of the Latin alphabet, it makes one wonder how such overwhelming number of character is organised. Ancient forms of Chinese characters are often mistaken for pictographs, hieroglyphs, and in extreme cases, letters. It is so, because our Western minds see differently than a Chinese or Japanese person. It also has to do with the nature of art and differences in aesthetics between the West and the East. In great simplification, Far Eastern art underwent a transformation from very abstract and symbolic to one infused with more realism. The art of the Western side of the world went through the exact opposite process; from realism to abstractionism. Consequently, a Chinese person looking at calligraphy work of the character 海 (sea) will sense the power of water, anger of waves, or suppleness of the water, its life giving ability, or element of clarity and spiritual purity. Westerner will see waves, water droplets, and sea foam. He or she will most likely seek a shape of something they can relate to in real life. Hieroglyph is from Greek, and it means “sacred writing”. Hieroglyphs differ from pictographs. One could say that they are onomatopoeic pictographs, i.e. characters that depict a given shape of an object and bear the same sound as that object. For instance a hieroglyph for a bird will resemble the shape of a bird and will have the sound “tweet”, etc. A pictograph is a character that is a physical representation of the shape of whatever it stands for. So a character for horse will resemble the shape or characteristic features of a horse. Chinese characters are divided into 6 groups. Those are: 1. Characters of pictographic origin (象形文字) 2. Phono-semantic characters (形声文字) 3. Compound ideographs (会意文字) 4. Rebus (phonetic loan) characters (仮借文字) 5. Indicative ideographs (指事文字) 6. Reciprocal meaning characters (転注文字) In Japan there is also one more category, known as National Characters (国字), i.e. characters artificially created from two or more characters or radicals. The above 6 groups are known as Liùshū (六書), i.e. “Six methods (of forming Chinese characters)”. The first book that mentioned this theory was the Confucian classic, the Book of Rites (周禮), also known as Rites of Zhou, from the 2nd century B.C.E. However, the first true analysis of this theory appears in the famous book by a Han dynasty philologist, Xǔ Shèn (許慎, ca. 58 CE – ca. 147), entitled “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analysing Compound Characters” (說文解字), written some 4 centuries later. By far, the largest group of Chinese characters are the phono-semantic characters. 85% – 90% of Chinese characters belong to this group. That includes a vast majority of the most ancient Chinese calligraphy scripts, such as bronze inscriptions (金文) or oracle bone script (甲骨文). Each of the phono-semantic characters is constructed of two compounds; one phonetic, and one semantic. Compound ideographs form a group of characters that are a combination of two or more pictographs, or characters whose meaning was based on an abstract concept. So, a character composed of two pictographs is NOT a pictograph (see also this article of mine). Phonetic loan characters define a group of characters that were borrowed phonetically to write another homophonic word. Consequently, their original meaning (ancient meaning) can be completely different from that such characters may represent in later historical stages. For instance, the character 早, initially it had nothing to do with the time (modern meaning: “early”, “early morning”, etc.). Its ancient meaning was “a flea” (蚤). Here is a quote from my upcoming book: “The original meaning of 早 (zǎo, i.e. “early”) was 蚤 (zǎo, i.e. “a flea), and vice versa (i.e. 蚤 often was used to express “earliness”),. Note that both characters have identical pronunciation and tone (zǎo). There are numerous examples of interchangeable use of both characters. For instance, in the Lí Lóuzhāng gōu (離婁章句) by Mèngzǐ (孟子, 372 – 289 B.C.E.), a Confucian philosopher, we read: 蚤起 (zǎoqǐ), i.e. “to wake up early”. “ Indicative ideographs are a group of characters that express simple abstract concepts. Here is yet another quote from my new book: “One of the theories says that the shape of kanji 一 (i.e. "one) is based on that of suànchóu (算筹), which were divination rods (small wooden sticks, similar in size to matches, but longer and thicker). They were also used for calculations in ancient China, hence their name: “counting rods”. Most of the literature offer an explanation that the character 一 is a pictograph of an extended finger. However, the analysis of other numbers (2 to 9 ) clearly supports the theory of it being an ideograph.

Reciprocal meaning characters are what you may refer to as the grey area of Chinese or Japanese linguistics. It is the smallest and the most confusing group of all six. Those are characters whose meaning was extended. For instance, a character 樂 means “music”, but it was extended to “fun”, “pleasure”, “comfort”, or even “happy”, “joyful”, etc. Due to the complexity of Chinese writing system, the extended period of thousands of years of evolution, and great variety of possible approaches to the subject of etymology, various sources may classify given character differently. |

Categories

All

AuthorPonte Ryuurui (品天龍涙) Archives

August 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed