|

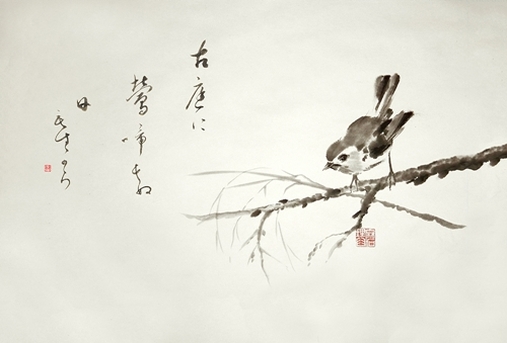

Aikidō is a type of martial arts, developed in Japan by Morihei Ueshiba (植芝 盛平). It is said, that Ueshiba was a simple man, though of great spiritual capacity. And so, Aikidō is just like its founder - simple. Or is it? Aikidōis based on the concept of redirecting the force of the attacker and changing the direction the enemy movement. Aikidō is not about aggression, competition or fighting. It is about attunement to nature, the flow of energy, peace and love. It is, as Ueshiba used to say himself, the perfect budo (武道; budo in Japanese means "martial art"). By "perfect" he meant "true" (真; real), as it conveyed the deep meaning which any type of martial arts should follow. Martial arts are not about (or should not) be about using force against others, but using force against self to avoid using it against anyone. Studying martial arts is a way of life. The path to understanding of such concept leads through hardship of training, strengthening one's spirit, meditation and perseverance. Through years of my martial arts studies, I have realised that there are only two types of martial arts students: 1. Those who go to martial arts trainings. 2. Those who never return from them. If one really comprehends the idea of martial arts, one never stops training. Training martial arts twice a week is not training, it is a waste of time, at least in my view. In this respect, Chinese or Japanese calligraphy is based on a very similar principles as Aikidō, or any other martial art. It is not art, not even an art within art, as we read in serious literature on the subject. Calligraphy is a way of life. It is a realm that once it is reached spiritually, it cannot be abandoned. I do not make time to study calligraphy. I make time to breathe, eat and sleep. I do not study calligraphy because I enjoy it. I study it because it is a living part of myself. If I ever stop, my soul dies. The quote of Morihei Ueshiba, which I write in the video posted above, can be applied to so many disciplines of life. That is because it is based on nature and its simple truths. He said: 「天地に氣結びなして中に立ち心構えは山彦の道」 "Let your mind and spirit be one with the the universe, stand in its centre, allow the the feeling of readiness to define your path, a path as sound and ubiquitous as a mountain echo. (path of the mountain echo is a path that reflects the changes of mind and body due to training, they become pure and unstoppable)" Morihei Ueshiba / "Essence of Aikido" / translation: Ponte Ryuurui.  Ink Treasures is an artistic project that I am currently working on together with an accomplished ink painter, Mariusz Szmerdt. We decided to combine our efforts, and not only co-create a series of artwork that would merge the traditional and modern ink painting and calligraphy art., but also tell you more about the history and secrets of both, and share some of our knowledge with those who are willing to study them. Our goal is not a specific genre, but a wide spectrum of themes, subjects, and techniques. The aim is to inject some new life into the traditional arts of ink painting and calligraphy. Our works will span from martial art motifs through female acts, abstract or fantasy art (you may expect a lot of dragons), to very traditional and subtle creations, such as you can see in the above picture., or even philosophical themes, such as Buddhism, Zen or Taoism. We will be opening a store with out art, too., which will be for purchase in various formats, be it electronic, raw (prepped for framing), or framed (modern or traditional, including Japanese hanging scrolls). We also except orders for commercial use, such as advertisement, books, posters, stock photos, business cards, concept art, etc. Please visit us on www.ink-treasures.com / facebook Ink-Treasures / Google+ Ink Treasures Our contact: [email protected] / [email protected] / [email protected] You can also mail me directly at [email protected] I am often asked by people who wish to study calligraphy, where and how they can learn. I may tell you right now, that there is no book in the world that can replace a good teacher. So, if you think you can study calligraphy from anything titled "Three easy steps to mastering Chinese / Japanese calligraphy", then you are very much mistaken. One day I was editing a video of my teacher writing a short phrase in seal script (篆書), and I suddenly realised how similar is the way that we both hold the brush. But not only that, even specific gestures, like repositioning of the brush in the hand, or subconscious "brush doodling" in the air, too. Then, I watched his arm, its position, the angle of the albow against the paper, brush grip, etc. I was astonished to see obvious similarities. Then again, our writing styles (書風, i.e. one's personal handriting style) differ. So, the technique is virtually the same, yet the outcome is not. Years ago, when I have only started to study caligraphy, I showed him one of my works. It was basically a copy of his own work. I thought he will be pleased, but he shaking his head in disapproval instead. He looked at me, seeing that I do not understand why he is not happy about it, and said: "Copying ancient masterpieces is a path to enlightenment. Copying your teachers' style is the end of the road. By copying my style you insult my teaching methods. Watch the technique, learn the basics, study the line, and then let your heart guide you. I can help you to build a boat, but you have to learn how to sail and maintain it yourself. Go and discover new lands, do not stick to the harbour". I have visited tens of calligraphy exhibitions in past years. Having the words of my teacher in my mind, I was shocked to see how many people copy their own teachers. The situation is serious to the extent that works displayed during some exhibitions are so similar, they all seem to be written by the same person. This is usually done to either tickle the teacher's ego, or simply get a praise, or even worse, to win a prize. Very sad indeed.

The technique is everything. Calligraphy is like martial arts. You study for a lifetime only to forget what you have learned. Let me tell you this again, you study for a lifetime only to forget what you have learned. You ought to write the calligraphy with your soul. There is no ink, no brush, no paper, no nothing. There is only Matrix. Then, and only then, you can call it shodō (書道; Japanese for "calligraphy", whcih could be interpreted as "the way of life through writing). Practice is not about perfection, but about freedom. If you move before you thought you needed to, then you are trully free. The calligraphy in the movie (above) is a quote of a famous philosopher, Albert Shweitzer. It reads: "Success is not the key to happiness. Happiness is the key to success. If you love what you are doing, you will be successful." 日本語: 成功は幸福の鍵ではない。幸福が成功の鍵なのだ。自分のやっていることが好きなら、きっと成功するだろう You can also see me writing this text with a ballpen, here. There is something about quotes that people like. Perhaps it is their amazing power of defining and summarising our paths, our goals, things we like and do not like, and so on. Those quotes assist us in expressing thoughts or wishes that, sometimes, we have troubles with compressing them into a smaller package, vocabularistically speaking. This new project of mine aims at gathering quotations and sayings of people from any ethnic, cultural, or historical environment, and putting their words on paper by means of Chinese or Japanese characters. The power of Far Eastern calligraphy resides in the complexity of the message of the brush strokes (or even pen / ballpen strokes, as you can see in this particual movie, below). Kanji or hanzi (or other writing systems, such as Japanese kana) can convey the emotions of the writer very well. The line flows down fromthe top of the page to the bottom like water. It can be a violent mouintain creek with many rapid curves and strokes, or a gently meandring stream thorugh a wide valley. It can be a roaring waterfall crushing anything in its path, or a still lake embracing the warm rays of lazy sun, setting down.

The script can be refined like mature clerical script (八分隷) or small seal script (小篆), where stokes are premeditated and they seem to be designed. It can be wild like cursive script (草書), or uneasy and illusively careless like ancient clerical script (古隷), to give only a few examples. Then, each of those has its variations. The ink is the limit. The quote in this movie is by Albert Schweitzer, an extremely talented man, who was a German theologian, pholosopher, physician, and a musician. It reads: "Success is not the key to happiness. Happiness is the key to success. If you love what you are doing, you will be successful." Albert Schweitzer Japanese translation: 成功は幸福の鍵ではない。幸福が成功の鍵なのだ。自分のやっていることが好きなら、きっと成功するだろう。 My path to happiness is marked by ink and brush. The day I had realised it, I was born again. I wish you will find yours. Chinese or Japanese calligraphy is not something that can be learned by reading books. It has to be practiced, on a daily basis. Calligraphy studies are all about copying ancient masterpieces. In Japanese it is called rinsho (臨書), which literally means "to look and write". There are various types of rinsho. For instance, what you see in the below movie is a classical rinsho, where I copy characters from an ink rubbing (拓本). Before each stroke, I look at the masterpiece, each brush movement counts. Another type of rinsho is hairin (背臨), which is performed after studying one classic for some time. Hairin is rinsho performed from memory, without looking at the masterpiece. But what is the real purpose of rinsho? Classical rinsho is essential to advancing in mastering calligraphy. It is not about crating the exact copy of given masterpiece (that is yet another type of rinsho, which is copying by means of a tracing paper). It is about the energy, spirit, dynamics, writing style, proportions, line characteristics, and so on. Rinsho means to copy the emotions, the mental state, the attitude, and the mood, that a given masterpiece consists of.

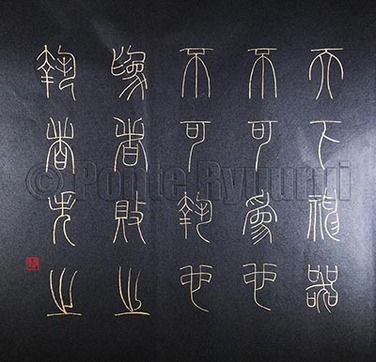

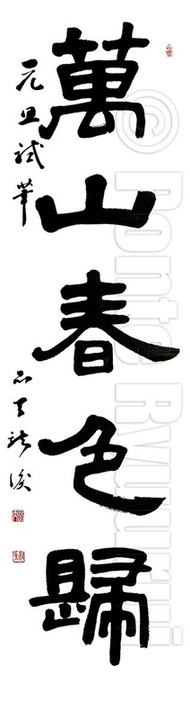

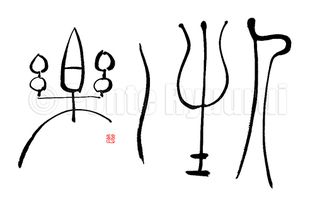

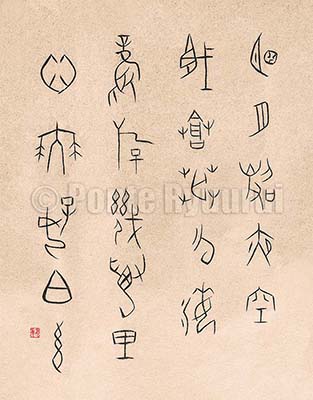

Rinsho is (or should be) the bread and butter of any serious or professional calligrapher, and it ought to be performed every day. Different masterpieces, different brushes, different ink, different paper, but the same aim - to mature as a calligrapher. Rinsho is the only way to developing an original and powerful calligraphy style (書風). This is the method used by thousands and thousands of calligraphers, including all the greatest ones out there. Calligraphy starts, continues and ends with rinsho. For rinsho studies, a knowledgeable teacher is a must. It is very easy to make mistakes, and some ink rubbings can be barely readable. Aside good calligraphy dictionaries, a proper guidance is invaluable. Otherwise, it is very likely one will be repeating one's own mistakes. every month, my teacher goes through hundreds of pages that I bring with me for him to discuss,. I cannot tell you how important it is to learn from a true Master of this art.  The calligraphy to the left depicts only a small fragment of a Chinese classic Daodejing (道德經; also read as Tao Te Ching), by Laozi (老子, c. 5th or 6th century B.C.). The Tao (or the Way), literally means "the path". In great simplification, Tao is a phenomenon, or a force, that cannot be defined, logically explained or mastered. It simply exists and it is out there for one to attune with it intuitively. Taoism, then, is a way of living, based on a concept of simplicity, attunement to nature, the concept of "non-acting". As Laozi has said himself: "The Tao that can be named is not the eternal Tao. The Name that can be named is not the eternal name. The nameless is the beginning of Heaven and Earth. the named is the mother of all things." Taoism, a philosophy and religion , had a great impact on arts and politics of China. That includes calligraphy. The essence of calligraphy is for one to be able to express one`s inner understanding of the art. The inner understanding becomes the Tao of calligraphy, a path of life one has chosen to follow. Each line, each stroke, and each page define the way of life of a given calligrapher. By looking at one`s calligraphy, we can understand and appreciate one`s Tao. Consequently, if one remains true to the Tao of calligraphy, one`s works will be powerful and truly masterful. Above calligraphy is written in small seal script (小篆). I used gold ink on black paper (20x20cm). The text reads: 天下神器、不可為也、不可執也。為者敗之、執者失之。 "The world is a sacred vessel. It should not be meddled with. It should not be owned. If you try to meddle with it, you will ruin it. If you try to own it, you will lose it." It is a quotation from Daodejing. To see this work in a larger format, please visit the coloured paper gallery. For those of you who enjoy meditation, I recommend you check the ultimate guide to Taoist meditation by Julian Goldie.  In Japanese, kakizome (書き初め) means "the first writing of the year". It became an official celebration between years 1844 and 1872, and originally was based on the kyūreki (旧暦), i.e. Japanese lunisolar calendar. Kakizome was endorsed by the famous Terakoya school (寺子屋) during the Edo period (江戸時代, 1603-1868). Initially, kakizome was a very formal and significant event. People gathered and wrote their first calligraphy works, either in front of the statues of Sugawara no Michizane (菅原 道真, 845 – 903 C.E.), who was considered the Scholar Sage, and who lived during the early Heian period (平安時代 794 – 1185 C.E.), or, on the ground of numerous Tanmangu Shintō shrines (天満宮), shrines devoted to the spirit of Michizane. Today, kakizome is still celebrated in Japan, although it is not as much popular as it was in its early days. Simply because, only a small percentage of people have time and patience to study calligraphy. Traditionally, phrases used for kakizome were short poems, very often related to upcoming spring, and welcoming the changes in weather and scenery. Such texts were written on paper, and then burnt during the Sagichō (左義長) fire festival. It is said, that if the wind lifts the ashes up into the skies, the caligraphy skills of whoever performed the ritual, will improve during the upcoming year. Every year, I participate in the national level kakizome calligraphy contest in Japan. The 2013 is the third consecutive year when my calligraphy work has won the gold award. This year I wrote a Chinese phrase: 萬山春色歸, which could be translated as "A mountain range has shifted its colours to a spring scenery". It is a fragment of a longer poem titled "early spring", from Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 - 907 C.E.) period, and I believe it was composed by Liu Wei (劉威). Calligraphy is in clerical script / 35x135 cm.  Yin and Yang (陰陽), the complementary forces (and not opposing, as many people erroneously believe) of the Universe we roam within, be it dead or alive. Yin and Yang should not be compared to the Western concept of good and evil, although both concepts are based on the idea of balance. Yin-Yang theory is ancient. Its origins go back to the 15th century B.C.E., during the Shang dynasty (1600 – 1046 B.C.E.). It had a global impact on so many disciplines of the Chinese, including medicine, martial arts, literature, politics, and so on. We find its traces in the Book of Changes (易經; Yi Jing, or I Ching) of which hexagrams that originated around the 3rd millennium B.C.E., were to be the cradle of Chinese writing system, as some sources incorrectly assume. Yin-Yang was in close relation to nature, which is not surprising at all. Virtually any ancient Chinese art or philosophy has similar background. That includes Chinese calligraphy, of which many brush strokes, for instance, were based on a falling rock, rapid creek, moves of a female dancer, or even the way geese turn their necks. In the 42nd chapter of Daodejing (道德經) by Laozi (老子, c. 6 or 5 century B.C.E.), we read: “The way begets one; One begets two; Two begets three; Three begets the myriad creatures. The myriad creatures carry on their backs the yin and embrace in their arms the yang and are the blending of the generative forces of the two.” Yin cannot exist without Yang, and vice versa. Those forces are so closely related, that one becomes the part of another. If the Yang gets stronger the Yin gets weaker. In calligraphy, the Yang can the paper, white, bright and absorbing the light. The Yin can be the ink, shiny, dark and supple. The relation between those two elements will have an impact on the final work, and the skill of maintaining the balance between those two is more intuitive rather than a solid knowledge than can be put down in books. Yin and Yang exist in everything. They cannot be defined, but only sensed. They cannot be measured, but can be subconsciously influenced. They cannot be fully mastered, but can be studied and meditated upon. And this is exactly how I would define the art of Chinese calligraphy. The work above reads Yang-Yin (read from right to left, as traditionally it should be). Written with a very soft, long and thin brush. Work is in stylised seal script (篆書), a script which stared to emerge in the last century of the Xia Dynasty (夏朝, 2070 – 1600 B.E.C.), even though its origins go back way back to the New Stone Age. To see this work in larger format, please visit my gallery, here  Woman`s body is one of the most beautiful and enchanting creations on Earth. Body art is a type of art that is create on or with (as a medium) a human body (source: Wikipedia). Some of the body art I have seen i was absolutely amazing. Human imagination is a bottomless vessel indeed. However, the calligraphy body art (I am referring here to Chinese calligraphy or Japanese calligraphy body art) is not a very popular subject. This may be due to the fact that not many people study the traditional art of Far Eastern calligraphy, or perhaps because those who do study it are of a senior age, and erotic body art is slightly ahead of their times or taste. The concept of my body art project is simply to amplify and complement woman`s natural beauty by a few or a few thousand brush strokes. The subject of my art and photography is a merge of those two. By "dressing" women in Chinese characters, their curves not only speak to our eyes, but also to our soul. The picture you see here is of my lovely and patient wife (writing alone took 2.5h). I covered her entire body in the text of Heart Sutra (般若心経), which is 268 characters long (without the title). It is one of the most popular, but also one of the most profound sutra texts. Copying a sutra text is a form of scared meditation, and it supposed to be performed with respect and dignity . I used the famous version attributed to Wang Xizhi (王羲之, 303 - 361 C.E.) of the Jin Dynasty (晉朝, 265 - 420), who is often referred to as the Calligraphy Sage (書聖). The original was written in semi-cursive script (行書). To see this image in larger format, please visit my body art gallery. To read the full text of the Heart sutra please see a work in the Ink Treasures gallery, which was co-created by myself and Mariusz Szmerdt (翔隼) To read more about Ink treasures project, please visit our site.  The above work is my copy of one of the masterpieces by Wu Dacheng (呉大澂, 1835-1902). This work is entitled "Red crane spring bronze pillar engraving" (白鶴泉銘銅柱銘), and it is written in seal script (篆書), or more precisely small seal script, which is one of the five major scripts in Chinese calligraphy. The original calligraphy was cast into one of the Zhou Dynasty (周朝, 1046 – 256 B.C.E.) bronze vessels (c. 5th century B.C.E.). Wu Dacheng started to learn Chinese calligraphy att a young age, and at the age of 17 he began his studies of seal script under Chen Huan (陳奐, 1786-1863). In later years, the seal script and seal carving, which is an art form closely related to seal script, became his specialty. Like many of the calligraphers of the Imperial China, Wu Dacheng was a politician, serving, among other posts, as governor of Guangdong Province.  Masterpieces by Wu Dacheng are used today for advanced calligraphy studies of this ancient script. His seal script is simply outstanding. Seal script is not only a crucial script for researching and understanding the etymology of Chinese characters, but alo invaluable for advancing in one`s technique of writing. I purposely used a long hair (5cm) thin (0.4cm) brush, to increase a difficulty of writing, and slow down the pace. Each line ought to be written with utmost care and concentration. If the focus is lost, the line will reveal the weaknesses of a calligrapher. To your left, you see a character 書 (to write / calligraphy) written in small seal script (小篆) by the Master Wu Dacheng himself. To view this work in a larger format, please visit my coloured paper caligraphy gallery.  Life is Joy (人生一楽) . This calligraphy work is written in stylised seal script ((篆書). Seal script is a large family of scripts, and can be split into two groups; great seal script (大篆) and small seal script (小篆). However, this calssification is not that easy as it would seem. Great seal script is rather difficult to define. To fully understand the complexity of the issue one would need to appreciet the political history of ancient China, and its influence on the art of Chinese calligraphy. In short, great seal script begins with bronze inscriptions (金文), which first appeared during late Xia dynasty (夏朝, 2070 - 1600 B.C.E.). Also, although oracle bone script (甲骨文) is often regarded as separate script, it could be classified as a member of the great seal script. Those are subjects for a longer articles, and I will be discussing those issues in greater details on the Ink Treasures site pages (it is an ongoing project between an ink painter, Mariusz Szmerdt (翔隼), and myself). Seal script is without a doubt the oldest linguistically mature script in Chinese calligraphy. It played a significant role in the history and development of the ancient China. To see the calligraphy artwork pictured above, please vising my gallery of calligraphy works on white paper, here.  A short poem which I wrote last year. It was inspired by one of the works of possibly the most cherished Chinese poet, Li Bai (李白; 701 – 762 C.E.). He lived during the Tang dynasty, the golden age of Chinese poetry, but also golden age of art in general, including calligraphy. English text: Bright moon illuminated the night skies Concealed in haze of vast sea of clouds Wind that travelled a few thousand miles Fluttered my mind light as silk Chinese translation: 明月照夜空 藏蒼茫雲海 風游幾萬里 心舞如白糸 Chinese translation by Yuki Mori (森由季). You can view this calligraphy in a larger format in a gallery, here |

Categories

All

AuthorPonte Ryuurui (品天龍涙) Archives

August 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed