I will cover the history of the standard script (楷書) in a separate article, but for the sake of placing it on the timeline of the history of Chinese calligraphy, let me just say that its origins go back to 170 B.C, which fact was confirmed in 1972, when the unearthed bamboo slips in Hunan province (湖南) were covered in a script that displayed evident features of modern standard script. Standard script is one of the most demanding scripts in Chinese calligraphy, and also most likely the first one a new calligraphy student is about to study. There are 8 core strokes in standard script, and they are known as the 永字八法 (8 laws of the character 永). Each of those strokes has many variations. The details of the 永字八法 will be also covered in a separate article. There are many different approaches to standard script, and there are numerous classics written in various styles. Also, it is important to state that the Chinese calligraphy aesthetics and Japanese calligraphy esthetics differ. Consequently, although the rules of writing remain similar (or the same) the appearance of both may differ. Consequently, although the rules of writing remain similar (or the same) the appearance of both may vary. There are many different approaches to standard script, and there are numerous classics written in various styles. Alhough I study calligraphy in Japan, my teacher as well as the calligraphy organisations I belong to, put a very strong emphasis on Chinese classics. Therefore, my style is a blend of both types of calligraphy. Nevertheless, I decided to base my tutorials on the masterpieces of Ouyang Xun (歐陽詢, 557–641 C.E.), a brilliant Tang dynasty calligrapher, whose standard script was unmatched (although he was not the only genius of standard script in the history of China). His style may sometimes seem to be slightly over the top and "too elaborated", but the balance, character structure, and the surgical precision of strokes are simply mind blowing.

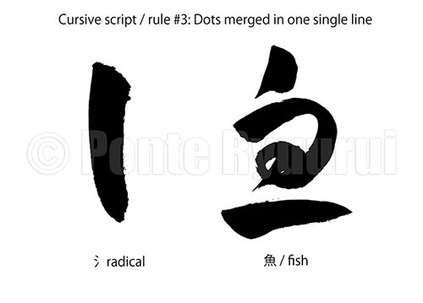

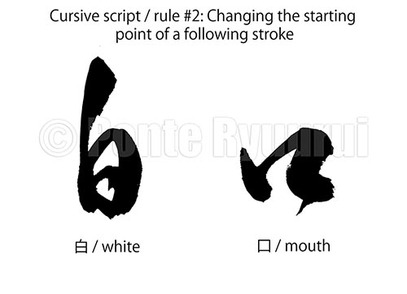

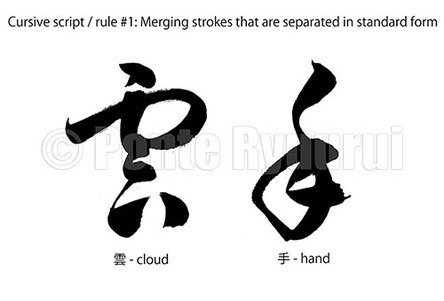

I remember I told my teacher once that I do not like a particular style of calligraphy (it was a Northern Wei standard script). He replied: "Studying only what you like is like taking a shortcut. Calligraphy is a journey. Those who are clever live by achieving an aim, and take the shortcut. Those who are wise, explore beyond their sight and become enlightened. " While studying standard script remember to: 1. write s l o w l y 2. learn the basic strokes 4. one stroke = one story 3. study different styles of standard script (do NOT copy me, copy the masterpieces) 4. never ever stop studying it, as standard script is the foundation of your skill with the brush  The third out of ten general rules of writing in cursive script (草書) . Radicals (radicals are components of Chinese characters) represented by dots in standard script (楷書), can be replaced with a single line. There are several types of radicals represented by dots. Radicals that contain two or more dots can be represented by a single line in cursive script. The diagram (left) and the movie (below) show only one type of such stroke in cursive script. There are many styles in calligraphy and also any of the radicals which are composed of dots can be written in a slightly different way. Being able to write the same character or the same type of radical n Chinese or Japanese calligraphy is a proof of mastery of this art, and shows a great knowledge and experience of the calligrapher. It also has a great impact on the appearance and aesthetical value of given masterpiece. It is important to realise that it is not the only one out there. Careful and diligent studies of cursive script are the key to learning and understanding other variants of this stroke.  The second rule of writing in cursive script (草書) (second of of ten in total; to read more about cursive script and the rules in general see my article here) is that some strokes can begin in the position where the previous stroke ended. This is quite a vital rule and goes along with all 10 rules of writing in cursive script. Those rules not only define the appearance and dynamics of the cursive script itself, but also influence the overall composition and mood. There is a technique known in Japanese as "unbroken line" (連綿体, lit. unbroken script). This technique applies to Chinese and Japanese calligraphy on many levels and I will discuss it in greater details in a separate article, however, the basic idea is to write calligraphy in a way to create an illusion or continuity, or actually merge all characters (or some) in one long brush stroke (where the brush does not leave the surface). As you can see in the diagram (above) and the video, the cursive script is all about the flow, but a flow that follows strict calligraphy rules (other than 10 general rules of writing cursive script). Those rules can be only mastered via studying and copying of ancient classical Chinese (or Japanese, in case of Japanese calligraphy) literature.

Cursive script (草書) evolved from the clerical script during the Han dynasty (漢朝, 206 B.C.E. - 220 C.E.). The embryo of cursive script is known in the calligraphy world as “draft script” (章草) which literally means “a draft (governed by) rules”. The use of character 章 (draft) is not accidental, however, and it is related to a name of the Emperor Zhang of Han (漢章帝, 57 - 88 C.E.), who introduced many governmental reforms, which required maintaining a close contact with all of the officials throughout his territory. He was the first ruler whom local officials could contact via letters written in cursive clerical script, i.e. “draft script”. It may seem not much of a change, but if we compare this to modern times, it would be similar to a situation when a city governor is contacting a president or a prime minister, by texting them from his iPhone. At that stage, draft script still bore visible elements of clerical script, yet was much smoother and curvier. Eventually, “draft script” developed into what we know today as cursive script. In the West, cursive script is often referred to as grass script, which is incorrect. Although the character 草 means "grass", its other meaning is "draft". Cursive script is one of the most difficult scripts to master. It is difficult to read, and difficult to write. A tiny movement of the brush tip in a wrong direction, can result in writing a different character from whichever was intended. Many people see this script as "easy", and attempt to write it without solid foundations in standard script (楷書) or semi-cursive script (草書), but I can tell you that it will only cause repeating and learning one's own mistakes. I will write on cursive script much more in the near future.

There are 10 major rules applying to cursive script: 1. Merging strokes that are separated in standard form 2. Changing the starting point of a following stroke 3. Dots merged in one single line 4. Straight lines are represented by curved lines, sharp corners by loops 5. Reduction of total number of strokes 6. Long lines are shortened or symbolised by dots 7. Complex radicals are significantly simplified 8. There is a change in a positioning of given stroke 9. Stroke order is altered 10. Starting point of an initial stroke is changed The diagram and video *above" explain the rule # 1.  Dots may be the smallest of the strokes in any script, but they are not necessarily the easiest to write. There are many rules to writing dots, and those depend on the script. In the case of clerical script, each dot should be (preferably) different from one another. The trouble is, that the writing technique remains the same (although there are several types of dots in clerical script, which will be covered by upcoming tutorials). What changes is the way we shape them with the brush. First of all, each dot begins with the reverse brush movement, which rule also applies to ANY stroke in clerical script. This technique is know as "reverse brush" (逆筆). Secondly, the dots should be written fairly slowly, in one stroke, and in a way to match the style of clerical script that we write (see my previous article to read more about types of clerical script). The three dots you see in the diagram (above) are a water radical, called sanzui in Japanese (氵), which means "three waters". This radical will reappear in my next tutorials, so you will be able to see other ways of writing it (including other scripts as well). Watch the video (above) to see how to operate the brush during writing of this type of dots in clerical script. Dots such as those in character 武 (the art of war / martial arts) or 龍 (dragon) will be written in a different way. See my upcoming tutorials to see how it is done.

There are many various types of vertical strokes in clerical script (隷書). The general rule of thumb is thus: every stroke begins with a reverse brush movement (see below video). However, the ways of writing the mid-sections and endings of the strokes may differ. Some have equal thickness and end with lifting the brush swiftly, whereas others may increase in thickness towards the end of the stroke (such as the one in the video below). Also, certain strokes can end with stopping and pressing, or even rotating of the brush tip. I will cover all types of vertical strokes of the clerical script in upcoming tutorials. To see other tutorials on calligraphy please see the learning category on this blog.

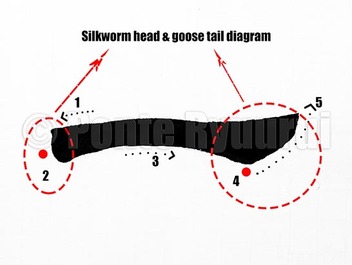

Clerical script (隷書) evolved from the great seal script (大篆). Its origins are dated back to the Warring States period (戰國時代, 475 – 221 B.C.E.) in China. There are two major types of clerical script. One is called ancient clerical (古隷), and the other is called mature clerical script (八分隷). The difference between those two, aside the various time periods throughout which they were used, is in writing technique, and , consequently, the appearance of both types of the clerical script. The technique shown in the picture (above) and the video (below) is applied in mature clerical script, however, it was initiated earlier on, and utilised for wring on long wooden slips (木簡). The name of this technique, the silkworm head and the goose tail (蠶頭雁尾), comes from the shape that those stroke resemble. Both techniques have many variants, and here you can see only one of them (the differences are in the appearance of both strokes, depending on the time period in calligraphy history, or the calligraphy style used for writing in the clerical script). Nevertheless, the technique of writing is always the same. In the above diagram you will notice numbers 1 - 5. They indicate the order of writing. Every stroke in clerical script begins with a reverse movement of the brush regardless of the direction of the stroke. This technique is known in Japanese calligraphy as gyakuhitsu (逆筆, lit. reverse brush),. One needs to crouch to make the leap graceful, as they say. This introduces a rhythm of writing which also slows down the brush in the process. The red dots (diagram) indicate where the brush should be stopped, briefly. All 5 movements ought to be completed in a single brush stroke (i.e. without lifting the brush tip off of the paper surface).

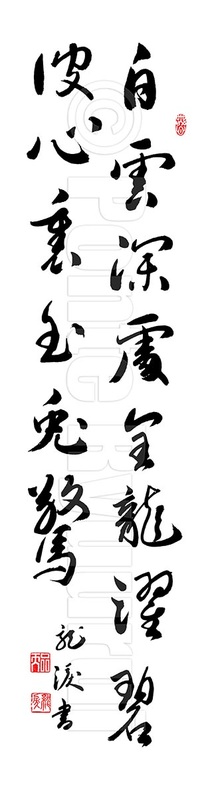

It is said, that mastering of this technique means that one has learned the basics of clerical script. It does not mean, however, that one has mastered the script itself. That comes with years and years of diligent practice.  Chinese or Japanese calligraphy art is all about immersion. One has to dissipate into one's element through studies. If you think of the studies as a commitment, your consciousness will disrupt the natural flow and obscure the true purpose. Writing calligraphy is not about focus or executing a premeditated design or a pattern. The aim of endless hours with the brush is to make you lose yourself in the studies. Do not remember, but forget instead. When you think what to write, it is your arm or mind that writes. When you stop thinking, then the Universe writes for you. To write smoothly, one has to become like water. It flows naturally, it is desire-free, and goes to where the geography of the land leads it to. The same with writing Chinese calligraphy. If the mind is knowledgeable, and the spirit pure and strong, the brush will glide like a dragon on the vast skies. The years of training is the geography of your art. Smoothen it with your studies, but do not forget about the beauty of mountains. When your spirit meets them, it will curve graciously. Your pure mind and clear soul is the water. Do not pollute it, do not regulate it. Let it remain like a child. Writing calligraphy could be compared to a strong feeling,. You are not supposed to control it. Let the emotions out. When you master the rules, and then forget them, it is when the journey begins. Stroll with your head upright, but do not be conceited. Chinese calligraphy is created in the absence of pride. Do not look back either, you are not going that way. My teacher once said: "I cannot write the way I was writing last year, and I do not know what my writing will be like next year. I do not focus on either. I do not wish to know what the spring will be like. I enjoy the winter, and welcome the change in weather with anticipation. This is what makes my life worth living for. Instead of wasting the energy on predicting, it is better to cherish what we have and learn how to adjust. This is the true way of living through writing. " Calligraphy teex: 白雲深處金龍躍 碧波心裏玉兎驚 Glittering sun was ascending like a golden dragon amongst the deep white clouds. Reflection of the astonished jade moon was sinking deep beneath the blue ocean waves It is a Zen phrase with multiple possible interpretations. Many thanks to Yuki Mori for finding this phrase, and her help with interpretation.

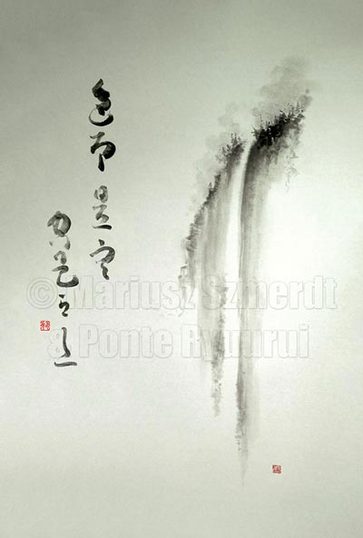

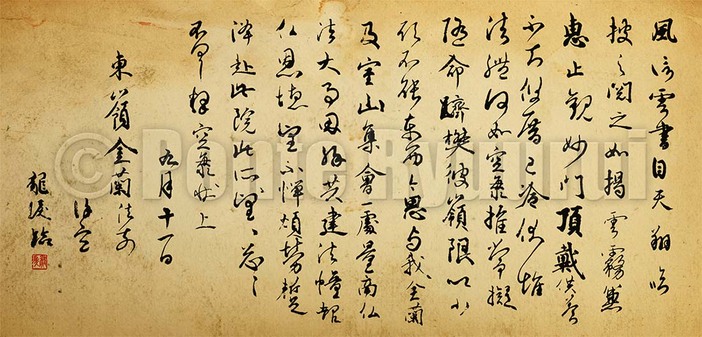

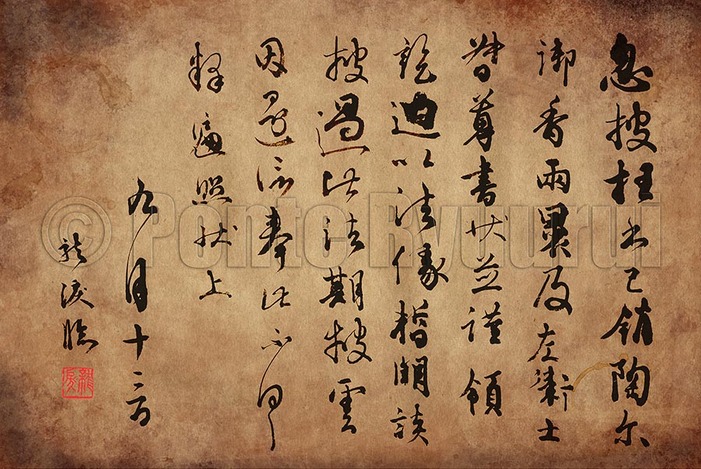

Together with Mariusz, we are working very hard on creating new exciting content for the Ink Treasures website. At the moment our focus is history related articles, as well as articles regarding the co-created art. Our aim is to create a comprehensive website network, with easy to understand and follow articles on the subject of ink painting and calligraphy. There are several new ideas in preparation, and although I cannot give you all the details yet, I can reveal a few things. First, this month we plan to launch our store, with all kinds of items for purchase. That will include art, custom art, designs, commercial and private orders, prints, and so on. Next, on May we are launching the forums, where people will be able to exchange their knowledge, experience, ask questions, share their art, or simply socialise. We have also started a cooperation with several institutions and artists in Japan and Europe. This year looks very promising, and we sincerely hope that you will enjoy what we are both preparing for you. Many thanks for your support! All updates are published on our Facebook fan page (see below), please give us your LIKEs!  Kūkai (空海, 774 - 835) is one of the most celebrated calligraphy Masters of ancient Japan. He was a Buddhist monk known as Kōbō-Daishi (弘法大師, i.e. The Grand Master Who Propagated the Buddhist Teaching). He was also a skilled poet, artist, and engineer. He was also the founder of Shingon Esoteric sect of Buddhism. It is also Kūkai who is said to be the creator of Japanese kana syllabary, which is one of the writing systems used in Japan until the present day (aside kanji), although it was never clearly confirmed by the historians and researchers. According to legends, Kūkai composed the famous Iroha poem, which is still in use for educational purposes in Japanese schools. Iroha contains all hiragana characters, but none of them is repeated. Its text reads: Although its scent still lingers on the form of a flower has scattered away For whom will the glory of this world remain unchanged? Arriving today at the yonder side of the deep mountains of evanescent existence We shall never allow ourselves to drift away intoxicated, in the world of shallow dreams. (translation by Professor Professor Ryuichi Abe)  Kūkai was travelling to China and spent there 20 years of his life. His knowledge and skill in Chinese calligraphy was outstanding. His writing style (書風) was heavily influenced by the masterpieces of Wang Xizhi (王羲之, 303–361), the calligraphy sage. He brought back with him many Chinese classics upon his return to Japan in 806 C.E. Kūkai, together with Emperor Saga (嵯峨天皇, 786–842) and Tachibana no Hayanari (橘逸勢 c. 782-842) was one of the initiators of the Japanese style in calligraphy, referred to as wayō shodoō (和様書道). Those three gentlemen are know today as "three brushes" (三筆) of the Heiyan period (平安時代, 794 - 1185). The above two calligraphy works are my humble coipies of the famous "Letter carried by the wind" (風信帖), which was a series of letters written to another Buddhist monk, Saichō (最澄, 767 - 822), the founder of Tendai (天台宗) Japanese school of Mahayana Buddhism. "Letter carried by the wind" is a national Japanese treasure, and it is often used for calligraphy studies in Japan. It style is a brilliant blend of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy styles, of which analysis can only enrich one's skills and horizons. See the Chinese and Japanese calligraphy history section to read more.  Many people ask me what is the purpose of my Chinese & Japanese calligraphy body art? What do I want to achieve or express through it? Some say, "oh so is this like in the movie Pillow Book by Greenway?" Well, when I started to create calligraphy body art, I was not aware of the existance of the Pillow Book movie at all. Someone told me about it, I watched it in fragments and regretted that I did. I should have known better, that it will be nothing else but some intellectual sweat, with a depressing theme lurking in the background, like a phantom of lost yawn. So what is the purpose of my calligraphy body art? Well, I am not sure that art needs a purpouse. It is such a journey to combine the arts of Chinese calligraphy with photography, and the beauty of woman's body. I absolutely love it. And what is more important for an artist than to enjoy the act of creation. The essence of calligraphy is not what you write, but how it is written. The energy and living spirt of the brush strokes, the composition, etc. Those are the crucial factors of a good calligraphy. When my teacher judges a calligraphy work, he starts from the composition, white space arrangement, character structure, meaning at the very end. If the calligraphy is written by a skilled artist, one does not need to understand what is written, to be able to feel its power. In calligraphy body art I adjust the composition to the natural curves of femal'e body, I blend both natural fenomena into one piece of art. I often use the Heart Sutra (or other sutra texts) text in my body art. Why? I love it. I love writing it, I love the message, and it calms me down when I write it. There is some unexplainable magic to it. And if someone asks me "why do you do that?", I reply: Heart Sutra can be written for protection. It protect the sexiness from fading away. Calligraphy line curves, and so does the female body. They talk to each other. Writing on skin is like designing a landscape. All elements must compliment one another, and stay in perfect harmony. Each person has a different character, so different writing style or calligraphy script can be chosen. Writing itself is not easy either. The skin moves, it is uneven, and the ink used is different than the traditional ink. It is all a great practice, too. Last but not least, I can tell you that body art calligraphy could be seen as a form of therapy. Chinese calligraphy studies are proven to be one of the most effective form of meditation and prolonging life, even more effective than Tai Chi. It is curious, that every single model tells me the same thing; "I loved the the brush tip movement on the skin. It was so soothing." If the text is long, such as Heart Sutra, and it takes a considerable amount of time to write, they simply doze off. |

Categories

All

AuthorPonte Ryuurui (品天龍涙) Archives

August 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed