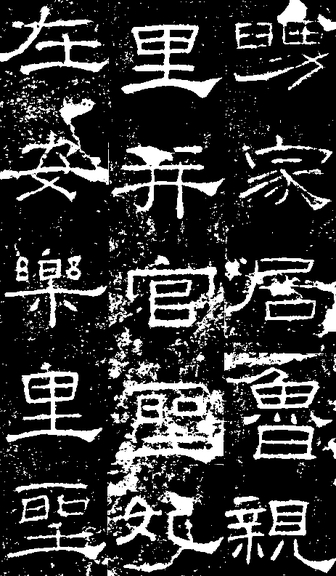

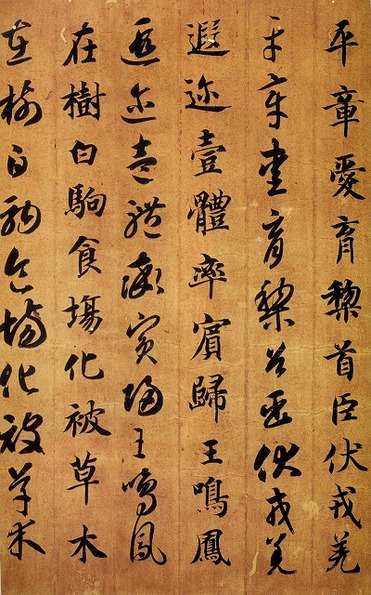

禮器碑 (Japanese: Reiki no Hi, lit. ritual dish stele) is a monument erected inside of the Mausoleum of Confucius. The author of the calligraphy work is unknown, though it is certain that the stele was erected during Late Han Dynasty (後漢, 25 - 220 C.E.), in 156 C.E. The monument was to celebrate the repairs of the Mausoleum of Confucius, and re-carving (renovation) of the stone ritual dish in particular. The text in Chinese calligraphy (clerical script) is a tribute to the family members of Confucius, and lists several names and various exploits and achievements of those individuals. The stone monument has two sides. Although both of them are carved in the mature clerical script, also known as 八分隷 (Japanese: happun rei), the style of writing is slightly different. The front side is more rigid in form, whereas the reverse side represents more relaxed Chinese calligraphy in clerical script. Both sides, however, characterise rather thin lines and light structure of the Chinese characters. If we compare this classic with similar monuments of Chinese calligraphy from the same period (such as 乙瑛碑 or 史晨碑 for instance), the delicate structure of Chinese characters in Reiki no Hi becomes even more evident. 禮器碑 is considered to be one of the most outstanding masterpieces written and carved in mature clerical, or even clerical script in general. It is a valid subject of studies by anyone who wishes to master Chinese calligraphy art.  Thousand Character Classic (千字文, Qiānzìwén) is one of the most important classics in Chinese literature, as well as a profound source of Chinese calligraphy masterpieces. It is said to be composed by Zhou Xingsi (周興嗣) during the first half of the 6th century C.E., upon the order of the Emperor Wu of Liang (梁武帝, 464–549), the founder of the Liang Dynasty. Emperor Wu was known to be well educated and enlightened ruler, who was promoting university level education, and, being a devout Buddhist, who opposed the animal sacrifices. It was Emperor Wu, who selected 1000 characters from works of the famous Wang Xizhi (王羲之, 303–361), hence the original name of the text (次韻王羲之書千字), which he suggested to his princes to be used for practicing calligraphy, and he asked Zhou Xingsi to compose a poetic essay out of them. The legend says that this task strained him so much, that Xingsi's hair turned completely white after completing it. The Thousand Character Classis consists of exactly 1000 Chinese characters, and what is more, none of those characters is appearing more than once in the entire text. The text itself is a poetic journey through the history of China, it contains information on geography, astronomy, ethics, politics, and so on. Thousand Character Classic was and still is used to teach kids Chinese characters. For calligraphers, this text is an invaluable source of knowledge, especially that so many great calligraphers copied it in their own style. What is more, the text usually was written in two or more scripts, which serves as a great reference for studying those. Placed side by side, Chinese characters in standard, semi-cursive, cursive, clerical or seal script, are a great way of familiarising with their various forms, as well as the ways of proper writing by the means of a calligraphy brush. The above picture is a fragment of Thousand Character Classic by Zhi Yong (智永, birth and death dates unclear), the great calligrapher and theoretician of the Sui Dynasty (581–618). Zhi Yong was also the author of the 永字八法 theory, i.e. "the eight principles of the character 永 (eternity)". This classic is known as 真草千字文, as it comes in standard (真) and cursive (草) scripts. Yong's handwriting style is bold and powerful, and his standard script often crosses the border with semi-cursive (行書). For those of you who wish to study contents of the Thousand Character Classic, there is an English translation created by the Nathan Sturman, of the University of Cambridge. |

Categories

All

AuthorPonte Ryuurui (品天龍涙) Archives

August 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed