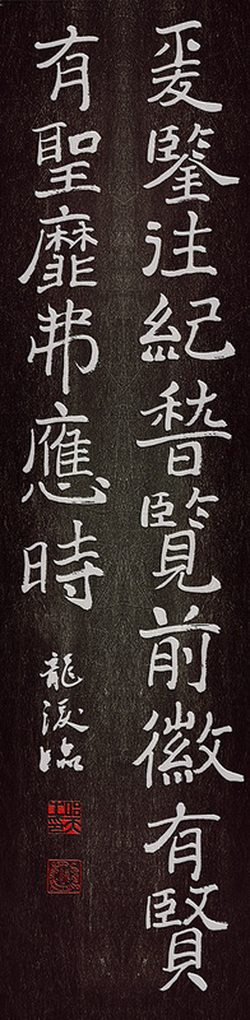

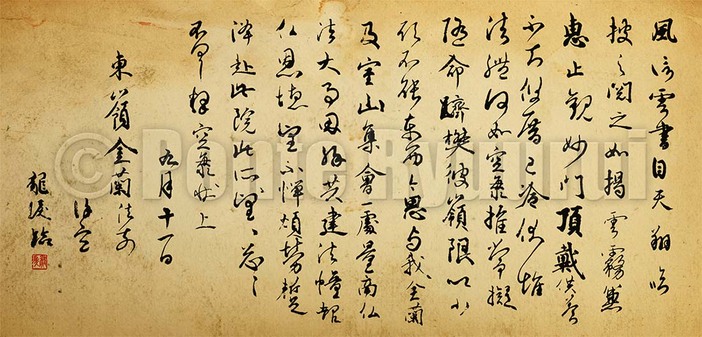

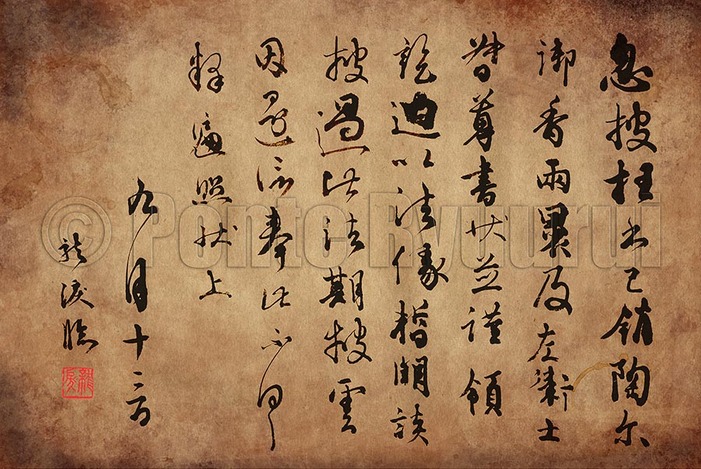

Chinese calligraphy of the Northern Wei dynasty (北魏, 386 - 534 C.E.) has one of the most powerful standard script styles in the history. If your calligraphy is lacking the bones and structure, you should definitely study masterpieces of this period. It happens so that from this month my obligatory montly subject for my next year's Master Instructor exams is one of the most famous classics of this period - the 鄭羲下碑 (Jap.: Teigi ka hi). The most characteristic features of this style are the rounded stroke (so called enpitsu in Japanese / 用筆) and the the strokes being between the standard and clerical scripts. The work to the left is my copy of this classic. Since the original is carved in a natural stone, I edited it in photoshop so it resembles characters carved on a hard stone-like surface. This work is available in a print form in my store, here.  Kūkai (空海, 774 - 835) is one of the most celebrated calligraphy Masters of ancient Japan. He was a Buddhist monk known as Kōbō-Daishi (弘法大師, i.e. The Grand Master Who Propagated the Buddhist Teaching). He was also a skilled poet, artist, and engineer. He was also the founder of Shingon Esoteric sect of Buddhism. It is also Kūkai who is said to be the creator of Japanese kana syllabary, which is one of the writing systems used in Japan until the present day (aside kanji), although it was never clearly confirmed by the historians and researchers. According to legends, Kūkai composed the famous Iroha poem, which is still in use for educational purposes in Japanese schools. Iroha contains all hiragana characters, but none of them is repeated. Its text reads: Although its scent still lingers on the form of a flower has scattered away For whom will the glory of this world remain unchanged? Arriving today at the yonder side of the deep mountains of evanescent existence We shall never allow ourselves to drift away intoxicated, in the world of shallow dreams. (translation by Professor Professor Ryuichi Abe)  Kūkai was travelling to China and spent there 20 years of his life. His knowledge and skill in Chinese calligraphy was outstanding. His writing style (書風) was heavily influenced by the masterpieces of Wang Xizhi (王羲之, 303–361), the calligraphy sage. He brought back with him many Chinese classics upon his return to Japan in 806 C.E. Kūkai, together with Emperor Saga (嵯峨天皇, 786–842) and Tachibana no Hayanari (橘逸勢 c. 782-842) was one of the initiators of the Japanese style in calligraphy, referred to as wayō shodoō (和様書道). Those three gentlemen are know today as "three brushes" (三筆) of the Heiyan period (平安時代, 794 - 1185). The above two calligraphy works are my humble coipies of the famous "Letter carried by the wind" (風信帖), which was a series of letters written to another Buddhist monk, Saichō (最澄, 767 - 822), the founder of Tendai (天台宗) Japanese school of Mahayana Buddhism. "Letter carried by the wind" is a national Japanese treasure, and it is often used for calligraphy studies in Japan. It style is a brilliant blend of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy styles, of which analysis can only enrich one's skills and horizons. See the Chinese and Japanese calligraphy history section to read more.  The above work is my copy of one of the masterpieces by Wu Dacheng (呉大澂, 1835-1902). This work is entitled "Red crane spring bronze pillar engraving" (白鶴泉銘銅柱銘), and it is written in seal script (篆書), or more precisely small seal script, which is one of the five major scripts in Chinese calligraphy. The original calligraphy was cast into one of the Zhou Dynasty (周朝, 1046 – 256 B.C.E.) bronze vessels (c. 5th century B.C.E.). Wu Dacheng started to learn Chinese calligraphy att a young age, and at the age of 17 he began his studies of seal script under Chen Huan (陳奐, 1786-1863). In later years, the seal script and seal carving, which is an art form closely related to seal script, became his specialty. Like many of the calligraphers of the Imperial China, Wu Dacheng was a politician, serving, among other posts, as governor of Guangdong Province.  Masterpieces by Wu Dacheng are used today for advanced calligraphy studies of this ancient script. His seal script is simply outstanding. Seal script is not only a crucial script for researching and understanding the etymology of Chinese characters, but alo invaluable for advancing in one`s technique of writing. I purposely used a long hair (5cm) thin (0.4cm) brush, to increase a difficulty of writing, and slow down the pace. Each line ought to be written with utmost care and concentration. If the focus is lost, the line will reveal the weaknesses of a calligrapher. To your left, you see a character 書 (to write / calligraphy) written in small seal script (小篆) by the Master Wu Dacheng himself. To view this work in a larger format, please visit my coloured paper caligraphy gallery. |

Categories

All

AuthorPonte Ryuurui (品天龍涙) Archives

August 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed