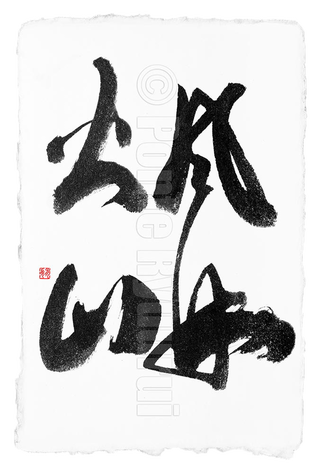

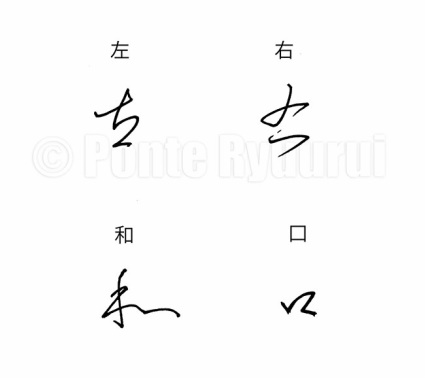

Cursive script is extremely intriguing. It is difficult to read, write and even to place its origin on a timeline (see this link to read my articles on the history of calligraphy and calligraphy scripts). Its definition is irregular and very flexible, just like its appearance. Even though it was, and still is in some cases, the most common script used daily by all the nations whose language is based on Chinese characters, not many of the modern native speakers can actually decipher it, let alone apply it with natural fluency in every day written communication. Modern civilization and computerisation of lives is to blame. It is no wonder, however, that the vast possibilities of expressing oneself are the reason for so many calligraphers to prefer to write in cursive hand. It is dynamic, abstract, passionate, favours subconscious creativity, and it is extremely expressive. Calligraphy written in cursive script may seem to be a maze of random brush strokes, or a late Picasso painting of anaconda snakes mating in their nest, but the paradoxical feature of it is that despite its random looks, cursive script requires a lot of precision and knowledge.  The studies of cursive script are long and taxing, starting with learning the basics of standard (楷書), semi-cursive (行書), and clerical scripts (隷書). Even though, historically speaking, cursive script preceded semi-cursive and standard scripts, it could be seen as an allegory for all three. The concept of cursive script is to emphasise the most characteristic features of the characters, and simplify them into a form that allows for faster and more fluent writing. However, those “shortcuts” are not any near being random, but rather carefully designed blueprints by some 2000 years of practical use. There are two major factors of cursive script that define its complexity. First one is that to writing in a way that brush is lifted from the paper surface as few times as possible (see my articles on the “unbroken line”). The second one is omitting and simplifying certain parts of a characters. As you may know, Chinese characters are built of radicals. Some characters may have completely different meaning, even if they share the same radicals (or radicals that look identically or nearly identically in modern standard script form). For instance 左 (hidari) means “left”, whereas 右 (migi) means “right”. The appearance of the 𠂇 (Japanese: sa, i.e. pictograph of a hand) seems to be nearly identical in both characters in the standard script, but its cursive forms will differ. This is because the etymology of the character 左 tells us that 𠂇 depicts the left hand, and in 右 it depicts the right hand. The stroke order of both differs in seal script (篆書), hence the difference in writing in cursive script. The stroke order of writing both characters in standards script also differs. Those may seem like small nuances, but such details have a massive impact on the composition and the flow of writng. Even in the case of a simple radical 口 (kuchi, i.e. “mouth”), the cursive forms might, or might not, have similar shapes. It all depends on the overall appearance of given character, or the calligraphy work composition. For example, it is possible that a cursive form of the Chinese character 口 in 右 may be written in a completely different way than that in 和 (wa, “harmony”), and usually it is so (see the diagram above). I invite you to view my tutorial on cursive script (videos included) |

Categories

All

AuthorPonte Ryuurui (品天龍涙) Archives

August 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed