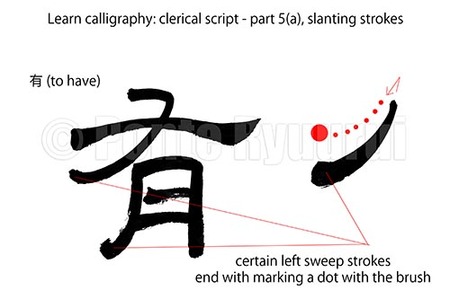

To view other tutorials on clerical script (隷書) please see here. There are five main types of strokes in each of the Chinese calligraphy scripts. Those are vertical strokes, horizontal strokes, slanting strokes, curved strokes, and dots. Each of those has multiples variants, further multiplied by the calligraphy script types. There are a few variants of slanting strokes on clerical scripts. They can be divided into two major groups, left slanting strokes and right slanting strokes. The pictured (above left) slanting stroke is a left slanting stroke, which means it slants to the left side. The key to understanding strokes in each script is to learn their characteristics and brush operating techniques. In clerical script, each stroke begins with a reverse brush movement (逆筆). However, not all strokes begin in the same manner. In fact, if you watch my other tutorials on clerical script you will notice those nuances. However, the major difference between the strokes lay in the way of leading the brush (送筆, lit. sending the brush), and ending the brush stroke (終筆). In case of this left slanting stroke, the brush pressure against the paper increases gradually, when the brush is on its way towards the end of the stroke, which causes the stroke to thicken. Finally, at the end of the stroke, the brush stops, is twisted (the brush tip marks a circle). During marking a circle, the brush pressure is lessened until the brush leaves the paper surface. See below video to see how it is done in practice. There are no more or less important strokes in Chinese calligraphy. All of them create the balance, build the character structure and even a single dot, which is badly placed or poorly executed, can ruin the whole work.

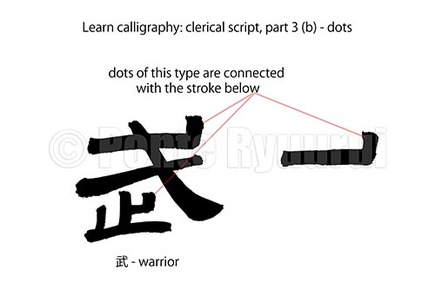

To view the part 3 (a) of this tutorial, as well as other tutorials on Chinese calligraphy scripts, please navigate to the calligraphy tutorials menu. To understand the differences between the clerical script (隷書) and the standard script (楷書) one has to learn about the origins of the scripts of Chinese calligraphy. Clerical script evolved from seal script (篆書), whereas standard script evolved from clerical script. There are many types of dots in clerical script, and they differ in the way of writing (the brush operating method) and, consequently, the shape. The type of dots shown in the diagram above, are remnants of the seal script form of certain strokes or radicals in seal script. The positioning of such dots, and their length or shape may be different, but they remain connected to the main structure of the character. In case of 武 (warrior), the dot in the top right-hand corner (the same that is written as a last stroke of the character - see below movie for details), was originally attached to the top part of the right slanting sweep stroke (written as second stroke in the video). Now, the 戈 in 武 is the pictograph of a long Chinese spear (鉾), and the dot stroke that you see in the clerical and standard script forms of 武 are the pictographic elements of the base of the spear blade.

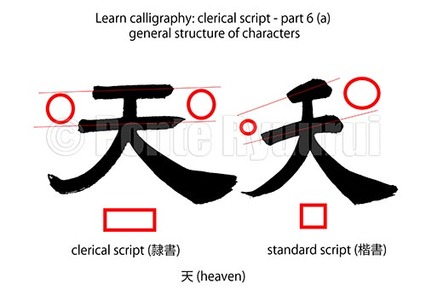

More tutorials on clerical script can be found here. Generally speaking, the structure of Chinese characters in clerical script (隷書) is squat, and horizontally rectangular. However, this rule mainly applies to the mature clerical script (八分隷). The characters in ancient clerical script (古隷) were often oblong, just like the script they evolved from - the seal script (篆書). In addition, the initial oblong structures of characters was imposed by the material they were written on - the long bamboo slips (木簡), although there4 were exceptions. One needs to remember that wooden slips were the most common writing material (aside silk), until the invention of paper around 3rd century B.C.E. The so called Age of Bamboo Slips lasted for some 2000 years. Together with the appearance of the silkworm head and goose tail strokes (蠶頭雁尾) in clerical script, the characters become wider and flatter. If you compare the shape of the character 天 (sky / void) in standard script (楷書) and clerical script (see the picture, above, and the video, below), you will surely notice the substantial structural differences The balancing of the clerical script is also different. Most of the vertical stroke are not only parallel to one another, but also at 90 degrees (or nearly 90 degrees) to the vertical strokes. Most of the greatest masterpieces of Chinese calligraphy were written in mature clerical script, during the Han Dynasty (漢朝, 206 BC – 220 C.E.). For this reason the structure of clerical script is mostly remembered as wide and squat.

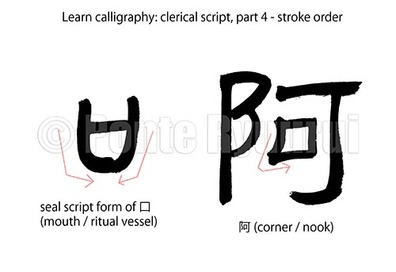

To view my other tutorials on Chinese & Japanese calligraphy please visit the learn calligraphy section. The stroke order in Chinese calligraphy is a very complex issue. It differs from country to country. China, Japan, Taiwan and Korea may use a different stroke order for the same character. For instance, the grass radical 艹 starts with the left-hand side vertical stroke in Chinese calligraphy, but in Japanese calligraphy the stroke order begins with the vertical line. Further, each of the five core calligraphy scripts have or may have different stroke order. If you look on my tutorials on cursive script, you will notice at least two rules out of ten which clearly indicate possibility of altering the stroke order, not only in relation to regular script (楷書), but within the cursive script itself. Clerical script stroke order is somewhere between seal script (篆書), which has very loose and not well defined stroke order to begin with, and the standard script (楷書). Because the clerical script evolved from the seal script, naturally some radicals follow not only the stroke order, but also the shape of the same in seal script. For instance, the stroke order in 口 (mouth / ritual vessel) is based on the way of writing 口 in seal script (see diagram or the video). Some of the older clerical script texts may even contain forms of 口 that look s exactly like the one written in seal script. It is impossible to lay down the stroke order rules in a short article, probably a book would not be able to cover those either. The only way of learning the proper stroke order is via studying the character structures in the ancient masterpieces. Comparing the forms of seal and clerical script of the same character, we can deduce the stroke order. On the other hand, stroke order in clerical script is much more relaxed and not as well defined as the stroke order in regular script. Certain radicals may have more strokes in clerical script that they have in regular script. In the case of 阿 (Japanese meaning: corner / nook), the 阝 (left village radical) radical, it has 3 strokes in clerical script and also 3 in standard script. However, the seal script form of this radical can have as many as 7 strokes.

In my upcoming tutorials on clerical script I will be coming back to the issue of stroke order numerous times. For the sake of a conclusion, I can say that the best way of learning the stroke order and the stroke number of characters, is to start with the standard script first, then semi-cursive, cursive, and finally clerical together with seal script. Stroke order may seem like a trivial issue, but it is the essential knowledge required for being able to write powerful calligraphy. The stroke order dictates the flow, the rhythm, the balance, the structure and, in result, the composition of the whole work. Learn it is as important as learning the brush operating techniques. So, learn it well.  Dots may be the smallest of the strokes in any script, but they are not necessarily the easiest to write. There are many rules to writing dots, and those depend on the script. In the case of clerical script, each dot should be (preferably) different from one another. The trouble is, that the writing technique remains the same (although there are several types of dots in clerical script, which will be covered by upcoming tutorials). What changes is the way we shape them with the brush. First of all, each dot begins with the reverse brush movement, which rule also applies to ANY stroke in clerical script. This technique is know as "reverse brush" (逆筆). Secondly, the dots should be written fairly slowly, in one stroke, and in a way to match the style of clerical script that we write (see my previous article to read more about types of clerical script). The three dots you see in the diagram (above) are a water radical, called sanzui in Japanese (氵), which means "three waters". This radical will reappear in my next tutorials, so you will be able to see other ways of writing it (including other scripts as well). Watch the video (above) to see how to operate the brush during writing of this type of dots in clerical script. Dots such as those in character 武 (the art of war / martial arts) or 龍 (dragon) will be written in a different way. See my upcoming tutorials to see how it is done.

There are many various types of vertical strokes in clerical script (隷書). The general rule of thumb is thus: every stroke begins with a reverse brush movement (see below video). However, the ways of writing the mid-sections and endings of the strokes may differ. Some have equal thickness and end with lifting the brush swiftly, whereas others may increase in thickness towards the end of the stroke (such as the one in the video below). Also, certain strokes can end with stopping and pressing, or even rotating of the brush tip. I will cover all types of vertical strokes of the clerical script in upcoming tutorials. To see other tutorials on calligraphy please see the learning category on this blog.

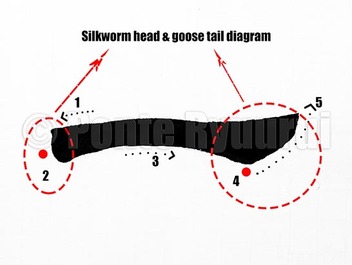

Clerical script (隷書) evolved from the great seal script (大篆). Its origins are dated back to the Warring States period (戰國時代, 475 – 221 B.C.E.) in China. There are two major types of clerical script. One is called ancient clerical (古隷), and the other is called mature clerical script (八分隷). The difference between those two, aside the various time periods throughout which they were used, is in writing technique, and , consequently, the appearance of both types of the clerical script. The technique shown in the picture (above) and the video (below) is applied in mature clerical script, however, it was initiated earlier on, and utilised for wring on long wooden slips (木簡). The name of this technique, the silkworm head and the goose tail (蠶頭雁尾), comes from the shape that those stroke resemble. Both techniques have many variants, and here you can see only one of them (the differences are in the appearance of both strokes, depending on the time period in calligraphy history, or the calligraphy style used for writing in the clerical script). Nevertheless, the technique of writing is always the same. In the above diagram you will notice numbers 1 - 5. They indicate the order of writing. Every stroke in clerical script begins with a reverse movement of the brush regardless of the direction of the stroke. This technique is known in Japanese calligraphy as gyakuhitsu (逆筆, lit. reverse brush),. One needs to crouch to make the leap graceful, as they say. This introduces a rhythm of writing which also slows down the brush in the process. The red dots (diagram) indicate where the brush should be stopped, briefly. All 5 movements ought to be completed in a single brush stroke (i.e. without lifting the brush tip off of the paper surface).

It is said, that mastering of this technique means that one has learned the basics of clerical script. It does not mean, however, that one has mastered the script itself. That comes with years and years of diligent practice. |

Categories

All

AuthorPonte Ryuurui (品天龍涙) Archives

August 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed