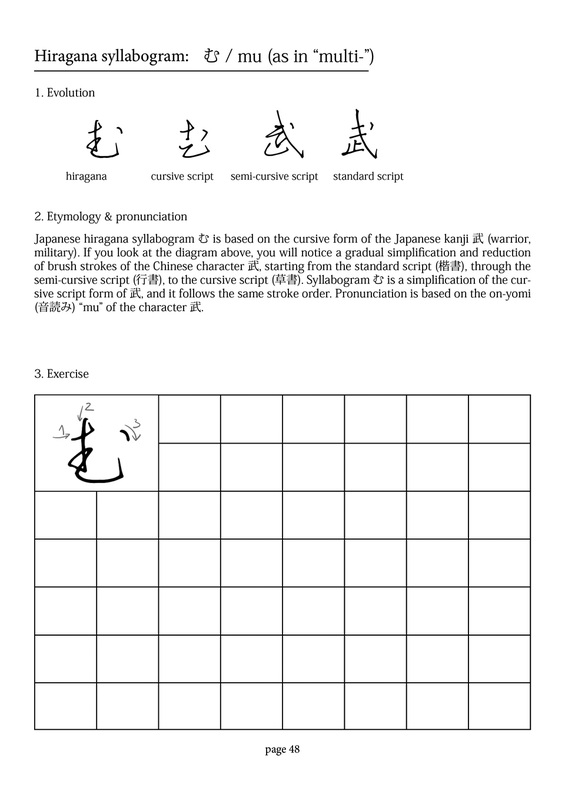

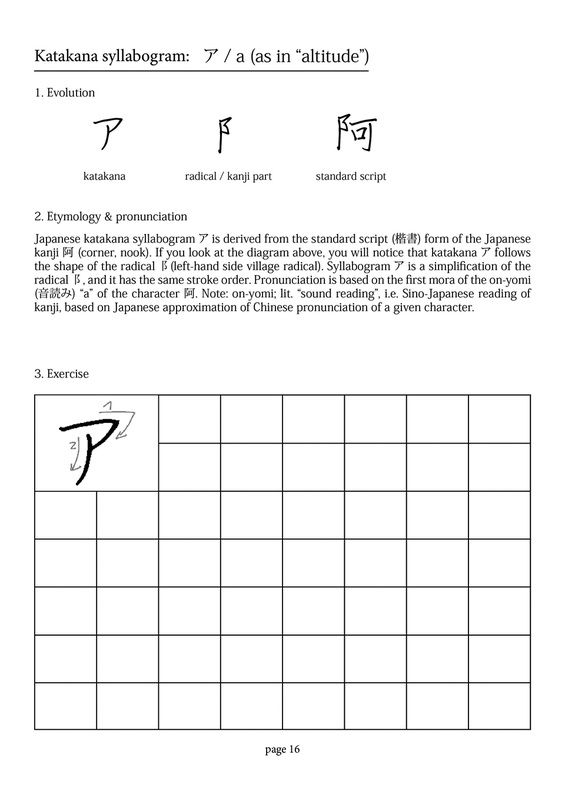

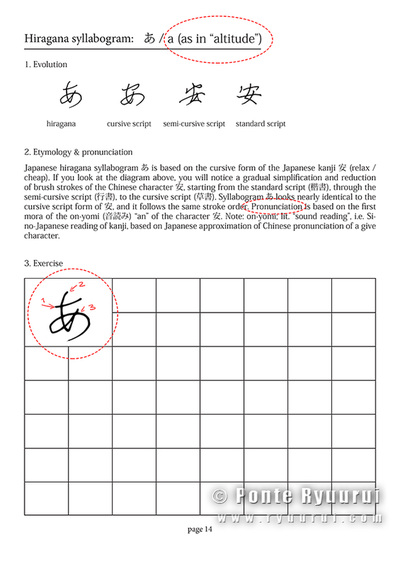

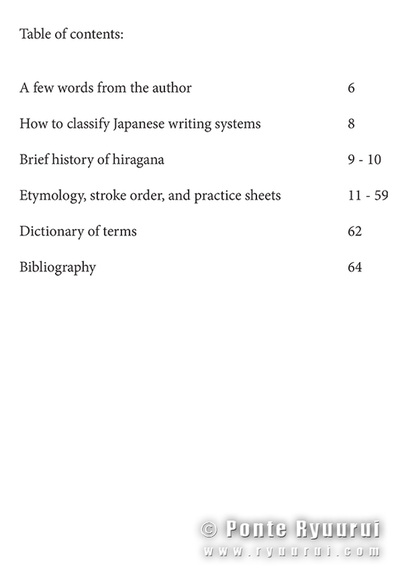

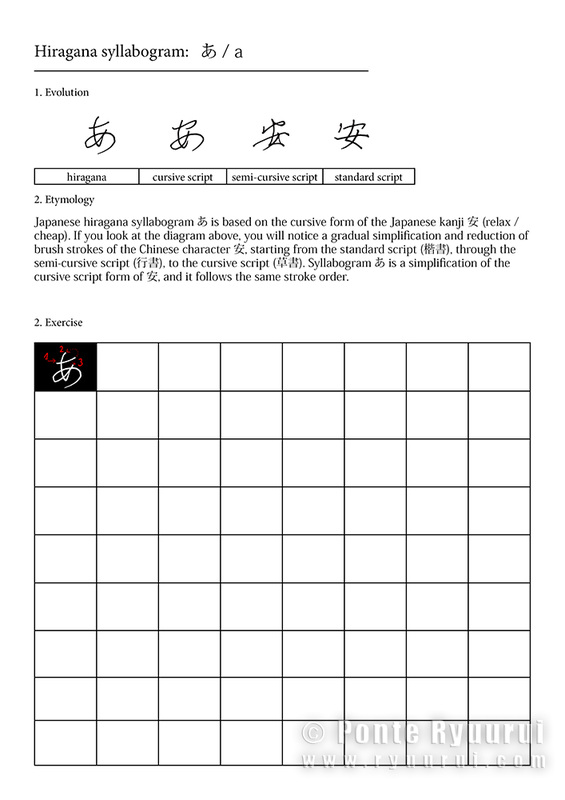

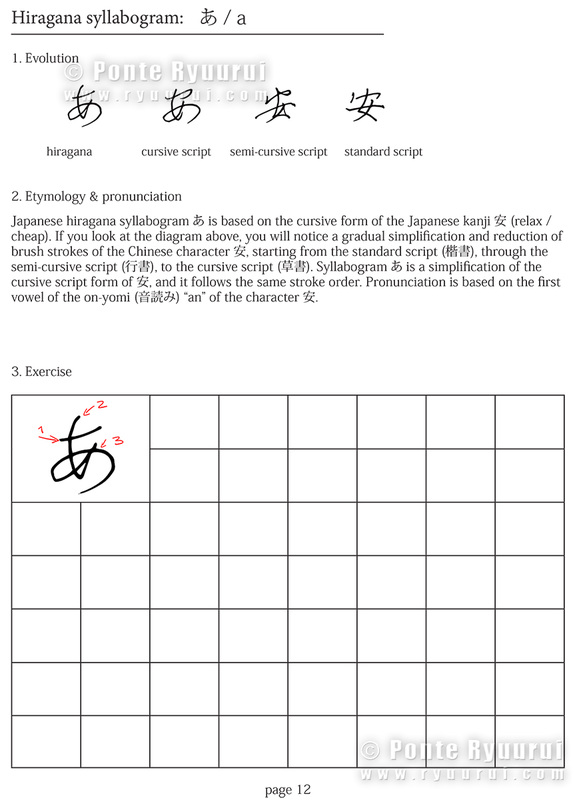

Officially published as of today! Learn Japanese Hiragana is one of three books on the subject of Japanese language and etymology that I have been working on for some time now. Although Learn Japanese Hiragana and Learn Japanese Katakana are separate and stand alone books, so it is possible to buy them as stand alone volumes. The most significant thing that distinguishes my books from any other hiragana and katakana textbooks out there, is that all and every single syllabary or a character was handwritten the way it should be. There is a huge discrepancy between a handwritten Japanese and computer fonts, and this subject is hugely neglected. When I started to study Japanese language 14 years ago, I always wished I had a book with handwritten examples of kanji, hiragana or katakana. But there is more. Not only each book has handwritten examples of hiragana and katakana, but also the kanji from which each of kana syllabaries evolved. Further, since hiragana evolved from kanji in cursive-script form, I included three different handwritten calligraphy scripts for each kanji to show a clear evolution from the standard script through semi-cursive to cursive script. In case of katakana I did the same thing with kanji radicals that each katakana evolved from. I have provided a detailed explanation of the origins of sounds of modern katakana and added a phonetic guidance based on pronunciation found in the online Oxford dictionary of English language. You should be able to replicate the proper sound of each katakana syllabary wit ease. In addition, I discuss the history of evolution of hiragana and katakana on a background of the history of Japanese calligraphy. I have included hand written stroke order charts of each syllabogram, with arrows pointing towards the correct direction of writing. All handwritten examples are based on traditional or historical Japanese calligraphy. Last but not least, I have included space for exercises, where you can practice your writing modelling yourself on the examples I have provided. Learn Japanese Katakana and Learn Japanese Hiragana is now available on my store on lulu.com, but in few weeks it will be available on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, etc. but if I receive enough requests I consider publishing it also in electronic form for Kindle, Nook, iBooks. Visit my page on Lulu bookstore to see preview of the book.  Officially published as of today! Learn Japanese Katakana is one of three books on the subject of Japanese language and etymology that I have been working on for some time now. Although Learn Japanese Katakana and Learn Japanese Hiragana are separate and stand alone books, so it is possible to buy them as stand alone volumes. The most significant thing that distinguishes my books from any other hiragana and katakana textbooks out there, is that all and every single syllabary or a character was handwritten the way it should be. There is a huge discrepancy between a handwritten Japanese and computer fonts, and this subject is hugely neglected. When I started to study Japanese language 14 years ago, I always wished I had a book with handwritten examples of kanji, hiragana or katakana. But there is more. Not only each book has handwritten examples of hiragana and katakana, but also the kanji from which each of kana syllabaries evolved. Further, since hiragana evolved from kanji in cursive-script form, I included three different handwritten calligraphy scripts for each kanji to show a clear evolution from the standard script through semi-cursive to cursive script. In case of katakana I did the same thing with kanji radicals that each katakana evolved from. I have provided a detailed explanation of the origins of sounds of modern katakana and added a phonetic guidance based on pronunciation found in the online Oxford dictionary of English language. You should be able to replicate the proper sound of each katakana syllabary wit ease. In addition, I discuss the history of evolution of hiragana and katakana on a background of the history of Japanese calligraphy. I have included hand written stroke order charts of each syllabogram, with arrows pointing towards the correct direction of writing. All handwritten examples are based on traditional or historical Japanese calligraphy. Last but not least, I have included space for exercises, where you can practice your writing modelling yourself on the examples I have provided. Learn Japanese Katakana and Learn Japanese Hiragana is now available on my store on lulu.com, but in few weeks it will be available on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, etc. but if I receive enough requests I consider publishing it also in electronic form for Kindle, Nook, iBooks. Visit my page on Lulu bookstore to see preview of the book. Thi is a continuation of my previous articles on my new book series on Japanese hiragana and katakana. To view previous posts, see here about the book concept in general, and here in regards to the book cover project. Below I am inserting a gallery of 3 images (click any to view). You can see what resources I used for writing the first book on Japanese hiragana. Then there is a sample page, and finally a table of contents page which should shed more light on what can one expect tom find inside. A few words regarding the sample page. Since I published the first draft I received great feedback from you guys, so thank you very much, and I decided to improve a few things. bibliography sample page table of contents I added an intuitive phonetic guide based on Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary's British and American English pronunciations of chosen words. This should clear a lot of confusion whenever a tricky pronunciation comes up (such as ゑ / "we"). I also explain where from each of the hiragana syllabograms take their sounds. For example, the hiragana syllabogram つ evolved from the cursive form of kanji 川, but none of the Japanese readings of this character is つ. The book is addresing address all of those issues.

Each hiragana syllabogram will have explained the stroke order and stroke direction, which is crucial for supporting a natural and comfortable way of writing. The diagrams will be large and clear. In table of contents you can see that there will be a general introduction, history of hiragana based on the evolution of Japanese calligraphy in Japan, as those are closely related. I am adding a short write up on the characteristics of the Japanese writing systems, and I define it very clearly what are kanji, what are kana's and what is the difference between them. Some of you probably know that I am working on several book projects. Today I decided to add one more, or actually two more. Last year I created a free tutorial on the origins of hiragana and katakana, but it is split into 96 separate articles, and all of the material is online. So, I decided to put together two small exercise books, one for hiragana and one for katakana. Books will include additional information, such as the history of both kana syllabaries, and a short dictionary that will explain all the difficult terms, etc. Below is a sample page from the hiragana book. It is still just a draft, but I wanted to hear your opinions. Perhaps I could improve it. Those books are aimed at those who wish to learn how to write Japanese kana's. Every single Chinese character in those books is hand written by me, and each script is based on historical forms of a given kanji. The same goes to the kana syllabograms. Books will be in A4 format, available in hard form and as a pdf download. Edit: here is an updated version of the same page, which I created after receiving valuable feedback from you guys. I really appreciate it!

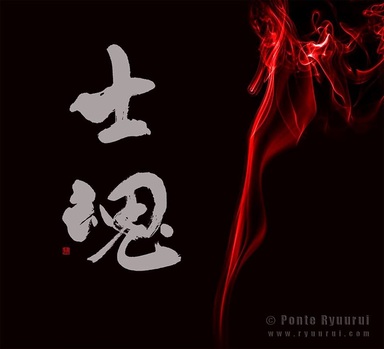

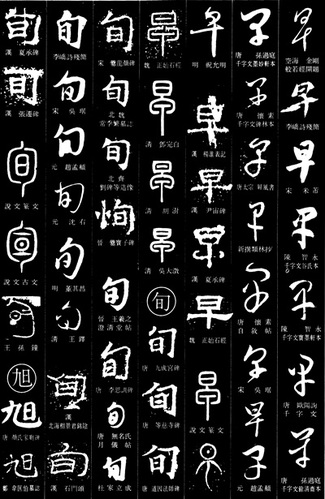

Each language has its own ways of expressing ideas and condensing thoughts or into laconic idioms or phrases. Since Japanese language is based on Chinese writing system, the idiomatic phrases can sometimes be very abstract or poetic. Such phrases are often based on Buddhist philosophy and way of seeing the surrounding world. Some are thousands years old, and thanks to the unique characteristic of Japanese kanji, the way such idioms were written has not changed at all for all those centuries. The data base of phrases and idioms that I am currently working on, is not just another dictionary of typical Japanese phrases or Japanese idioms. i am carefully selecting each phrase. Also, every single Chinese character is individually linked to my favourite online kanji dictionary, wwwjisho.org (created by Kim Ahlström) which is one of the largest and brilliantly designed interactive kanji dictionaries. Moreover, the readings of the idioms or words that you will find in my dictionary, are given in English and Japanese hiragana. Each of hiragana syllabograms is also linked individually to the Japanese kana database that I have created. This data base consists of handwritten characters, etymology of each syllabogram, and stroke order charts with correct hiragana and katakana stroke order. As you can imagine, linking all those characters is quite a taxing job for me, I am sure it will not only help those who study Japanese (or Chinese), but also will assist all those of you who are new to the wonderful world of Chinese characters and Japanese kanji, yet are fascinated by its exotic originality, to better understand its mechanics, and how words and ideas are conveyed through Chinese characters. There is also a separate section with Japanese calligraphy jargon explained. Some of the phrases will be linked to my store with calligraphy art or photography & calligraphy art combined, where you can purchase prints with your favourite phrase, and decorate your home, or offer it as a gift. If you like a particular phrase and want me to write it for you in Japanese calligraphy, then feel free to message me at [email protected] Errare humanum est, so if you do spot a mistake, or an error in linking, please let me know by mailing me at [email protected] or messaging me on facebook at Ponte Ryuurui or Learn Japanese and Chinese calligraphy Last but not least, since it is my first post in 2014, I would like to wish you all a happy new year. I would also like to thank Snow Forest (雪森) for her assistance with selecting some of the idioms and phrases, as well as with determining the correct reading (many idioms have special readings, which are often unknown even to native speakers). pictured calligraphy: 士魂 - samurai spirit  Chinese writing is the oldest writing system on our planet. It precedes Sumerian cuneiform by at least some 1500 years, going all the way back to the Yangshao culture (仰韶文化; 5000 – 2000 B.C.E.). It is also the most advanced writing system that human race managed to develop. We know for a fact that the total number of Chinese characters exceeds 90,000. If one compares this against the 23 letters of the Latin alphabet, it makes one wonder how such overwhelming number of character is organised. Ancient forms of Chinese characters are often mistaken for pictographs, hieroglyphs, and in extreme cases, letters. It is so, because our Western minds see differently than a Chinese or Japanese person. It also has to do with the nature of art and differences in aesthetics between the West and the East. In great simplification, Far Eastern art underwent a transformation from very abstract and symbolic to one infused with more realism. The art of the Western side of the world went through the exact opposite process; from realism to abstractionism. Consequently, a Chinese person looking at calligraphy work of the character 海 (sea) will sense the power of water, anger of waves, or suppleness of the water, its life giving ability, or element of clarity and spiritual purity. Westerner will see waves, water droplets, and sea foam. He or she will most likely seek a shape of something they can relate to in real life. Hieroglyph is from Greek, and it means “sacred writing”. Hieroglyphs differ from pictographs. One could say that they are onomatopoeic pictographs, i.e. characters that depict a given shape of an object and bear the same sound as that object. For instance a hieroglyph for a bird will resemble the shape of a bird and will have the sound “tweet”, etc. A pictograph is a character that is a physical representation of the shape of whatever it stands for. So a character for horse will resemble the shape or characteristic features of a horse. Chinese characters are divided into 6 groups. Those are: 1. Characters of pictographic origin (象形文字) 2. Phono-semantic characters (形声文字) 3. Compound ideographs (会意文字) 4. Rebus (phonetic loan) characters (仮借文字) 5. Indicative ideographs (指事文字) 6. Reciprocal meaning characters (転注文字) In Japan there is also one more category, known as National Characters (国字), i.e. characters artificially created from two or more characters or radicals. The above 6 groups are known as Liùshū (六書), i.e. “Six methods (of forming Chinese characters)”. The first book that mentioned this theory was the Confucian classic, the Book of Rites (周禮), also known as Rites of Zhou, from the 2nd century B.C.E. However, the first true analysis of this theory appears in the famous book by a Han dynasty philologist, Xǔ Shèn (許慎, ca. 58 CE – ca. 147), entitled “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analysing Compound Characters” (說文解字), written some 4 centuries later. By far, the largest group of Chinese characters are the phono-semantic characters. 85% – 90% of Chinese characters belong to this group. That includes a vast majority of the most ancient Chinese calligraphy scripts, such as bronze inscriptions (金文) or oracle bone script (甲骨文). Each of the phono-semantic characters is constructed of two compounds; one phonetic, and one semantic. Compound ideographs form a group of characters that are a combination of two or more pictographs, or characters whose meaning was based on an abstract concept. So, a character composed of two pictographs is NOT a pictograph (see also this article of mine). Phonetic loan characters define a group of characters that were borrowed phonetically to write another homophonic word. Consequently, their original meaning (ancient meaning) can be completely different from that such characters may represent in later historical stages. For instance, the character 早, initially it had nothing to do with the time (modern meaning: “early”, “early morning”, etc.). Its ancient meaning was “a flea” (蚤). Here is a quote from my upcoming book: “The original meaning of 早 (zǎo, i.e. “early”) was 蚤 (zǎo, i.e. “a flea), and vice versa (i.e. 蚤 often was used to express “earliness”),. Note that both characters have identical pronunciation and tone (zǎo). There are numerous examples of interchangeable use of both characters. For instance, in the Lí Lóuzhāng gōu (離婁章句) by Mèngzǐ (孟子, 372 – 289 B.C.E.), a Confucian philosopher, we read: 蚤起 (zǎoqǐ), i.e. “to wake up early”. “ Indicative ideographs are a group of characters that express simple abstract concepts. Here is yet another quote from my new book: “One of the theories says that the shape of kanji 一 (i.e. "one) is based on that of suànchóu (算筹), which were divination rods (small wooden sticks, similar in size to matches, but longer and thicker). They were also used for calculations in ancient China, hence their name: “counting rods”. Most of the literature offer an explanation that the character 一 is a pictograph of an extended finger. However, the analysis of other numbers (2 to 9 ) clearly supports the theory of it being an ideograph.

Reciprocal meaning characters are what you may refer to as the grey area of Chinese or Japanese linguistics. It is the smallest and the most confusing group of all six. Those are characters whose meaning was extended. For instance, a character 樂 means “music”, but it was extended to “fun”, “pleasure”, “comfort”, or even “happy”, “joyful”, etc. Due to the complexity of Chinese writing system, the extended period of thousands of years of evolution, and great variety of possible approaches to the subject of etymology, various sources may classify given character differently.  There is much confusion on the subject of how to classify Japanese kanji or, in other words, Characters of Han China (漢字). I often see websites, or even books, devoted to Japanese language and culture, where we read this and that about Japanese letters, or Chinese symbols, or anything equally intellectually challenged. To elaborate on the title of this article, we need to look at the definition of the word "letter" first. Letter is a stand alone linguistic unit of a written language representing one or more of the sounds used in speech. Letters form alphabets. Letters DO NOT bear any meaning. The Japanese word 文字 (moji) means "a character" or "characters". It is often shortened to 字. But the character 字 also means "letter", "symbol", "word", etc. It would seem that the phrase "Japanese letter", or "Japanese symbol" is yet another erroneous translation from Japanese to English, or from Chinese to English, as if we did not have enough of those laying about (see my article where I talk about the "grass script"). Chinese character (or Japanese kanji), unlike letters, may have multiple meanings, and they DO NOT form an alphabet, but a writing system based on logographic characters (or ideographic logograms). Chinese characters are also known as sinographs. There are six major groups into which one can divide Japanese kanji. I will discuss this in separate articles. Last but not least, only because you see an ancient Chinese character, such as the one you see in the picture above, it does not necessarily mean it has to be a pictograph. This particular kanji is 森 (Japanese: mori, i.e. woods), and although it is composed of three pictographs of a tree (木, Japanese: ki), it belongs to a group of characters that are a combination of two or more pictographs, or characters whose meaning is based on an abstract concept. This group is known in Japanese as 会意文字 (kai-i moji). Characters of pictographic origin form one of the six groups of Chinese characters. In other words, some of the Chinese characters are pictographs, but this group of characters is not that large at all. There are over 90,000 (yes, you read correctly, it is ninety thousand) Chinese characters out there. 85% - 90% of them belong to a group known as the samasio-phonetic compound characters (形声文字, Japanese: keisei moji). Such characters, as the name suggests, are composed of semantic and phonetic radicals. Summarizing, do not trust blindly "serious" literature on the subject of Chinese or Japanese linguistics. For example, I can tell you now, that ALL books that I saw on the etymology of Chinese characters are either entirely incorrect, or incorrect in a large part. Those are either based on no research at all, or a research done so poorly, that the authors should pay damages to whoever buys their books. Often times authors base whatever they write on other English authors, who are also wrong, or on outdated research preceding the discovery and analysis of the oracle bone script (甲骨文). I am currently working hard on changing this unacceptable status quo, on which subject I will be able to update you in next month or two. |

Categories

All

AuthorPonte Ryuurui (品天龍涙) Archives

August 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed