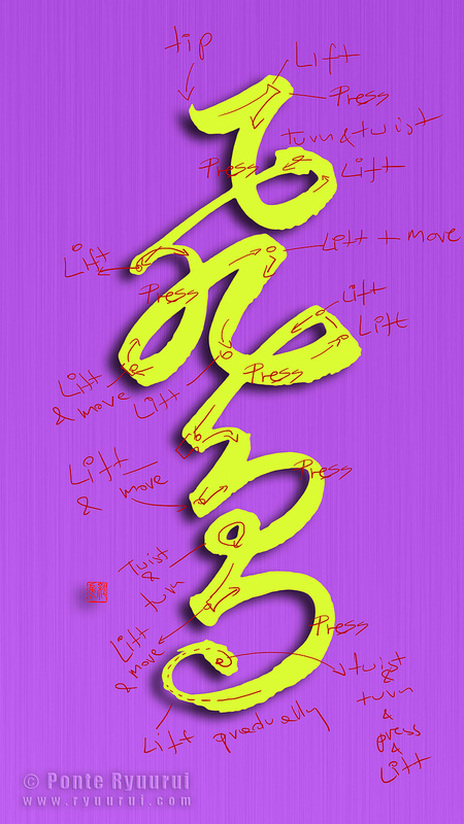

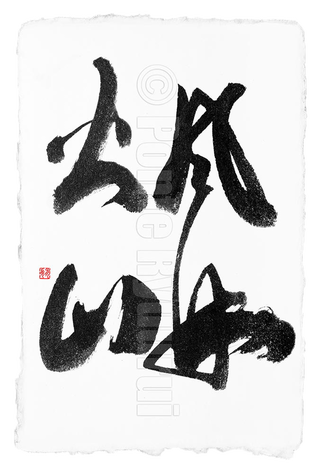

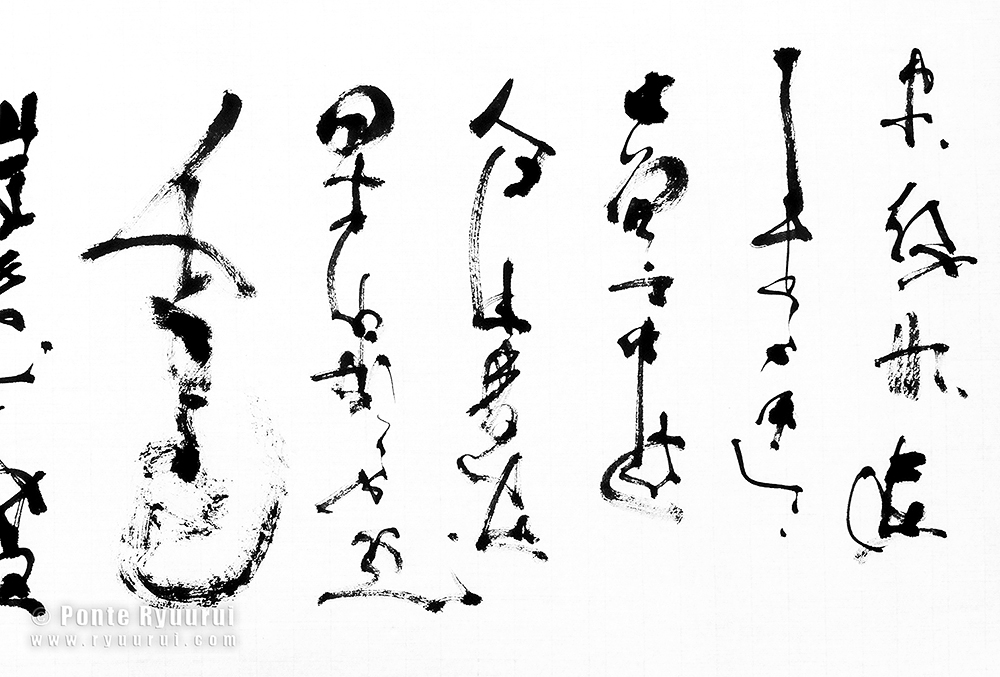

The main purpose of this book is not to teach Japanese kanji, but help you to understand and appreciate the vast complexity and philosophical and cultural depth of Chinese writing system. I talk in details about the etymology of 50 chosen characters, at a speed of one character per chapter. There are over 400 illustration inside the book, and all of them are not only actual historical characters taken from ink rubbings of outstanding Chinese and Japanese calligraphy masterpieces, ranging from 1600BCE to 19th century CE., but each of those illustrations has a detailed description regarding who wrote it and when, with other interesting historical facts or trivia, either about the classic or the author. The true value of this book is that the key contents are based purely on Japanese or Chinese literature, and not translations into other languages. I bring you knowledge that is hidden behind the language barrier for most of the Western world. One of my main sources for this book were publications by one of the greatest modern scholars of the etymology of Chinese writing, Shirakawa Shizuka (白川静, 1910 - 2006), who sadly passed away in 2006. His books are hugely valued not only in Japan but also in China and Taiwan. Since his publications are quite encyclopedic, and are based on numerous abbreviations and connotations, even native speakers whose field is Japanese or Chinese language, find those books difficult to read. I invested a great amount of time and effort, and backed it up with my years of experience in the field of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy, to explore a lot of side topics and intriguing fact on the subject of origins of kanji, and included them in my book. Etymology of Japanese kanji - in-depth analysis of selected characters is a book aimed at anyone who is interested in Chinese or Japanese language, or history of ancient China and Japan, or any enthusiasts who appreciate the culture and philosophy or the Far East. The title of this book was the most difficult thing to decide on, since it is impossible to talk about Japanese kanji without discussing Chinese characters, which in some cases are the same thing, and in others are different. I decided on Japanese kanji in the title, mainly because I live in Japan and this is also where I study calligraphy. If you have any questions regarding the book, feel free to send them directly to me or leave a comment below. I created this short clip today to show those of you who study Chinese or Japanese calligraphy the brush flow during and in between the brush strokes in semi-cursive script. If you are not acquainted with the concept of unbroken line, I strongly suggest you read and watch my other video tutorials on the subject. It is absolutely essential not only for semi-cursive script studies, but Chinese or Japanese calligraphy in general. The classic I write in this video is composed out of characters written by the calligraphy sage, Wang Xizhi, of the Jin Dynasty in China. Enjoy! For more calligraphy tutorials and information, see the learning section on this website. Photo editing & Chinese and Japanese calligraphy tutorial videos Buy fine art calligraphy prints at my store in my store on Fina Art Amercia.  I was writing some calligraphy works for Snow Forest's aroma therapy oil project, and when I created this calligraphy I realised that this is a perfect example for illustrating how does the calligraphy brush tip move during writing. The magic of Chinese calligraphy is based on many factors, but one of the key elements is the mastery of the brush pressure control against the paper surface. This is especially visible in cursive script, which is very dynamic, and the line rapidly changes the direction or thickness. Look at the remarks I made on the pictured single stroke calligraphy work, and note how much is happening from placing the brush on the paper surface to lifting the tip at the end. The brush tip is moving like an elevator, it goes up and down all the time, it also twists and turns, which moves are coordinated with the entire arm, as the wrist barely moves during writing. Those are microscopic movements, but the brush is held at its end of the axis, and the brush tip is at the opposite side. A tiny movement of the calligrapher's arm can cause massive alterations to the brush strokes. Those moves are subconscious, not thought out, and completely intuitive. How does one achieve such coordination? Here is your answer. Non-character calligraphy is practiced mostly in China and Japan, though it is a very rare style of Chinese calligraphy. It is of rather modern origin, and it slightly overlaps with the avant-garde calligraphy style. Its basic concept is to prove that the beauty of calligraphy does not have to be tied to the balance and shape of the Chinese characters, but it lives as raw energy in the dynamics of calligraphy brush strokes. Extended studies of Chinese classics, and countless hours spent on writing, allow a calligrapher to utilise his knowledge in such a type of art which is completely disconnected from the language itself, and it proves without a shadow of doubt, that Chinese calligraphy is written with a soul, not the hand.

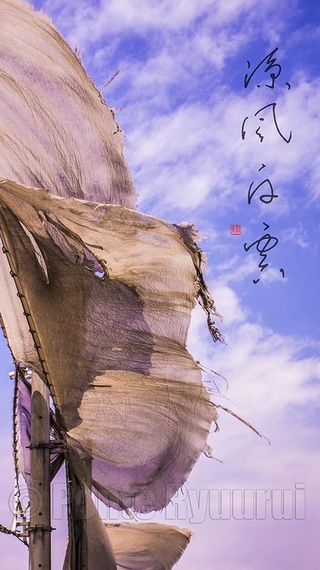

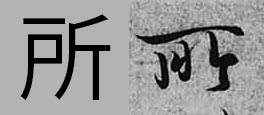

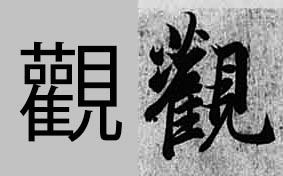

Pictured calligraphy (fragment) has no semantic content. It is a record of a state of mind.  When I started to study photography in greater depth, I realised how much it has in common with the art of Chinese or Japanese calligraphy. Photography is all about light, composition, negative and positive space ratio, a message it carries, impact of the image on a viewer, and story telling via the personal style of a photographer. But what about calligraphy? Well, the balance between the ink and white paper space counts for the negative and positive space, then we have the Chinese characters carrying a message. While the energy and power of the brush strokes catches the viewer's attention, the calligrapher's skill and personality defines the originality of given calligraphy. However, photography, similarly to the majority of Western painting styles, is speaking through an image that is far more easily recognisable by the audience. We see a photography or a painting, and we immediately link what we see to real life objects or situations we encountered. On the other hand, Chinese calligraphy can be quite intimidating for many reasons. It is not only extremely abstract, but also unreadable for most of the people, even including the native speakers (especially the younger generation). I am often asked, if I can understand all the ancient masterpieces that I study. No I do not. Only those who study Chinese calligraphy in depth know, that the secret to understanding calligraphy art is not being able to read or translate the text, but to read it without reading. In other words, being able to read the energy of the brush strokes, or to be entranced by the white space. Those are the elements that speak to me from a calligraphy masterpiece, not the words. The combination of calligraphy and photography arts is a perfect duo. It conveys a message in both abstract and more literal form. I also believe that it serves perfectly as a bridge, between what the eyes can recognise, and what only soul can read. It is not only a fantastic aestethical journey, but also a mutual educational experience (between the artsit and the audience). Calligraphy text: 涼風白雲 (cool breeze and white clouds)  Unlike Chinese calligraphy, Japanese calligraphy utilises several different writing systems. Those are: kanji (漢字), katakana (片仮名), and hiragana (平仮名) the writing systems known to anyone who studies modern Japanese language, but also hentaigana (変体仮名), manyōgana (万葉仮名), and so on. To understand the history of Japanese calligraphy, it is best if you read my article on the subject. However, for the sake of better understanding of this article, it is necessary to say a few more words in regards to those writing systems. Japanese kanji evolved from Chinese characters. Since Japanese grammar is completely different from the Chinese one, there was a need for developing a writing system to be used for distinguishing prefixes, grammatical expressions, etc. Today, hiragana syllabary is used for dealing with grammatical issues, and katakana is mostly used for writing foreign names and as phonetic explanatory notes. Historically speaking, various different types of Japanese calligraphy have evolved, depending on which writing system, or writing systems, are applied in a single calligraphy work. For instance, the calligraphy you see in the picture (above), is a typical kana majiri bun (仮名交じり文), which stands for: "a text that is a mixture of kana and kanji". Another type would be chōwatai (調和体), which stands for "harmony of scripts". Such calligraphy can include both kana syllabaries and kanji, similarly to kana majiri bun, but the forms of characters or syllabopgrams are based on those found in classical literature. In this respect kana majiri bun is a modern form of chōwatai. Last but not least, there is also kana script (かな), which refers to calligraphy written exclusively in hiragana and / or hentaigana. Pictured calligraphy: 果てしない夏(の)愛 (everlasting summer love) In modern times we all study from printed books or data published on the internet. There is no such things as handwritten books, and the only time we are in touch with handwritten form of any language is mostly through our own writing. When learning kanji (i.e. Chinese characters) we refer to shapes of characters printed in books or dictionaries. Our brain registers those shapes, and that is how we right those character by hand. In China or Japan, kids learn how to properly write characters with a brush, which is an obligatory subject. Now, one of the reasons, of such classes still existing, is that people learn much faster through hands-eyes coordinated actions. The other reason is much more practical. Many Chinese characters or Japanese kanji have very different appearance in a handwritten form. Certain radicals (i.e. parts from which kanji are constructed) can have multiple forms. For example, 心 (heart, mind, spirit, etc.), can be written as 心, 忄, or 㣺. All those forms are derived from the ancient divinatory script (甲骨文) and bronze texts (金文) of the Shang and Zhou dynasties (from ca. 6th century B.C.E. onwards), as well as the later clerical script (隷書). Other radicals can appear in a simplified form, to allow for easier reading. If you look at the images below, I picked three random characters from the famous "Preface to the Poems Collected from the Orchid Pavilion" (蘭亭集序) by Wang Xizhi (王羲之, 303–361). This masterpiece is written in semi-cursive script (行書), which is the script most of the people would choose for casual writing. Looking from the left to right we have 集 (to gather), 所 (place) and 観 in its traditional form of 觀 (appearance). The bottom radical 木 (tree) written at the bottom of a character will (in most cases) be a combination of 十 with two dots on both sides. This way of writing is more aesthetically appealing, and the whole structure looks much lighter in form, which improves the overall composition of given kanji.

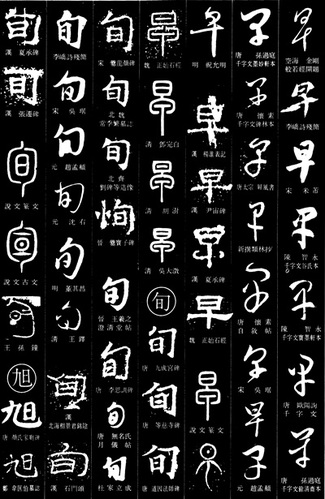

If you look at the second character (所) it looks very differnt from its computer version. This particular form was derived from the later clerical script (隷書) forms of 所, particularly the top long horizontal stroke. The third character's top-left part is known as the ”grass crown" radical, which also has many versions (艸,艹,艹,艹). It is almost never written the way you see it in the computer font. It would simply be too heavy and unsophisticated. Then the two 口 (mouth) radicals are simplified to dots, which is common in semi-cursive writing. There are thousands and thousands of characters that look differently in a written form, and the only way to master those forms is through copying or viewing the ancient masterpieces, as well as the analysis of different calligraphy script.  Chinese writing is the oldest writing system on our planet. It precedes Sumerian cuneiform by at least some 1500 years, going all the way back to the Yangshao culture (仰韶文化; 5000 – 2000 B.C.E.). It is also the most advanced writing system that human race managed to develop. We know for a fact that the total number of Chinese characters exceeds 90,000. If one compares this against the 23 letters of the Latin alphabet, it makes one wonder how such overwhelming number of character is organised. Ancient forms of Chinese characters are often mistaken for pictographs, hieroglyphs, and in extreme cases, letters. It is so, because our Western minds see differently than a Chinese or Japanese person. It also has to do with the nature of art and differences in aesthetics between the West and the East. In great simplification, Far Eastern art underwent a transformation from very abstract and symbolic to one infused with more realism. The art of the Western side of the world went through the exact opposite process; from realism to abstractionism. Consequently, a Chinese person looking at calligraphy work of the character 海 (sea) will sense the power of water, anger of waves, or suppleness of the water, its life giving ability, or element of clarity and spiritual purity. Westerner will see waves, water droplets, and sea foam. He or she will most likely seek a shape of something they can relate to in real life. Hieroglyph is from Greek, and it means “sacred writing”. Hieroglyphs differ from pictographs. One could say that they are onomatopoeic pictographs, i.e. characters that depict a given shape of an object and bear the same sound as that object. For instance a hieroglyph for a bird will resemble the shape of a bird and will have the sound “tweet”, etc. A pictograph is a character that is a physical representation of the shape of whatever it stands for. So a character for horse will resemble the shape or characteristic features of a horse. Chinese characters are divided into 6 groups. Those are: 1. Characters of pictographic origin (象形文字) 2. Phono-semantic characters (形声文字) 3. Compound ideographs (会意文字) 4. Rebus (phonetic loan) characters (仮借文字) 5. Indicative ideographs (指事文字) 6. Reciprocal meaning characters (転注文字) In Japan there is also one more category, known as National Characters (国字), i.e. characters artificially created from two or more characters or radicals. The above 6 groups are known as Liùshū (六書), i.e. “Six methods (of forming Chinese characters)”. The first book that mentioned this theory was the Confucian classic, the Book of Rites (周禮), also known as Rites of Zhou, from the 2nd century B.C.E. However, the first true analysis of this theory appears in the famous book by a Han dynasty philologist, Xǔ Shèn (許慎, ca. 58 CE – ca. 147), entitled “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analysing Compound Characters” (說文解字), written some 4 centuries later. By far, the largest group of Chinese characters are the phono-semantic characters. 85% – 90% of Chinese characters belong to this group. That includes a vast majority of the most ancient Chinese calligraphy scripts, such as bronze inscriptions (金文) or oracle bone script (甲骨文). Each of the phono-semantic characters is constructed of two compounds; one phonetic, and one semantic. Compound ideographs form a group of characters that are a combination of two or more pictographs, or characters whose meaning was based on an abstract concept. So, a character composed of two pictographs is NOT a pictograph (see also this article of mine). Phonetic loan characters define a group of characters that were borrowed phonetically to write another homophonic word. Consequently, their original meaning (ancient meaning) can be completely different from that such characters may represent in later historical stages. For instance, the character 早, initially it had nothing to do with the time (modern meaning: “early”, “early morning”, etc.). Its ancient meaning was “a flea” (蚤). Here is a quote from my upcoming book: “The original meaning of 早 (zǎo, i.e. “early”) was 蚤 (zǎo, i.e. “a flea), and vice versa (i.e. 蚤 often was used to express “earliness”),. Note that both characters have identical pronunciation and tone (zǎo). There are numerous examples of interchangeable use of both characters. For instance, in the Lí Lóuzhāng gōu (離婁章句) by Mèngzǐ (孟子, 372 – 289 B.C.E.), a Confucian philosopher, we read: 蚤起 (zǎoqǐ), i.e. “to wake up early”. “ Indicative ideographs are a group of characters that express simple abstract concepts. Here is yet another quote from my new book: “One of the theories says that the shape of kanji 一 (i.e. "one) is based on that of suànchóu (算筹), which were divination rods (small wooden sticks, similar in size to matches, but longer and thicker). They were also used for calculations in ancient China, hence their name: “counting rods”. Most of the literature offer an explanation that the character 一 is a pictograph of an extended finger. However, the analysis of other numbers (2 to 9 ) clearly supports the theory of it being an ideograph.

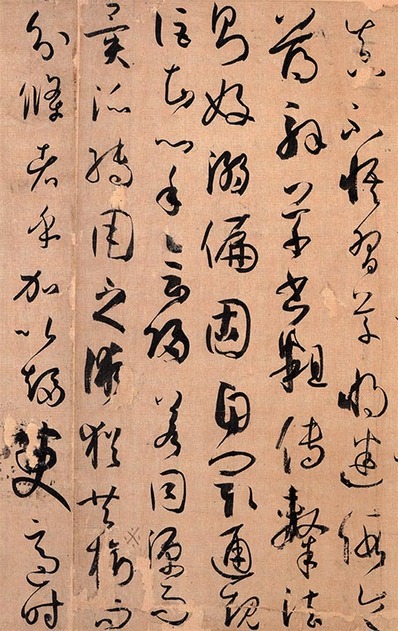

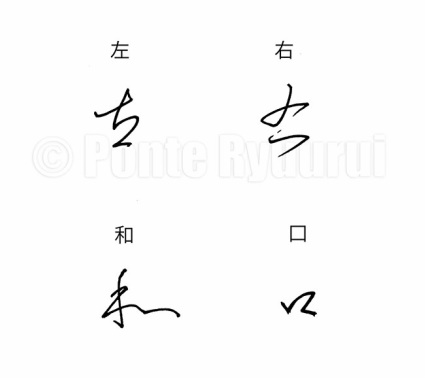

Reciprocal meaning characters are what you may refer to as the grey area of Chinese or Japanese linguistics. It is the smallest and the most confusing group of all six. Those are characters whose meaning was extended. For instance, a character 樂 means “music”, but it was extended to “fun”, “pleasure”, “comfort”, or even “happy”, “joyful”, etc. Due to the complexity of Chinese writing system, the extended period of thousands of years of evolution, and great variety of possible approaches to the subject of etymology, various sources may classify given character differently.  Writing in cursive hand could be compared to a skilled martial artist, who does not think, but reacts instinctively when performing various techniques. Constant and extensive studies are the only path to mastering this script. In the history of Chinese calligraphy art, there were a few calligraphers whose cursive script skills were beyond human perception. Those were, Dù Dù (杜度, early 1st century C.E.), Cuī Yuàn (崔瑗, 77-142 C.E.) , Zhāng Zhī (張芝, died 192 C.E.), the sage of cursive hand Zhāng Xù (張旭, 8th century C.E.), who was also the creator of wild cursive hand (狂草, kuáng cǎo), Huái Sù (懷素, 737–799), the brilliant drunk monk, the Two Wangs: Wáng Xīzhī (王羲之, 303–361) , the sage of calligraphy, and his son Wáng Xiànzhī (王獻之, 344 – 386), Sūn Guòtíng (孫過庭, 646–691), also known as Sūn Qiánlǐ (孫虔禮) whose Treaties on Calligraphy (書譜) is not only a well of knowledge on calligraphy but also a bible of cursive script forms (see a fragment of this masterpieces in the picture to the left), and Xiān Yú Shū (鮮于樞, 1246 – 1302). Naturally, this list does not exhaust the list of brilliant Chinese calligraphers, who excelled in cursive script. You can view and read about the masterpieces of some of those Masters, here. Very popular way of studying cursive script is by performing rinsho (臨書, lit. “facing and writing”, i.e. copying of masterpieces) of “Thousand Characters Essay” (千字文), an essay (written as a rhyming poem) composed of 1000 non repeating Chinese characters, in the first half of 6th century C.E., by Zhōu Xīngsì (周興嗣, died in 521), upon the order of the Emperor Liáng Wǔ (梁武帝, 464 - 549), for the sole purpose of calligraphy education. Many great calligraphers copied this text imbuing it with their own style, writing it in two, three or even more forms, one aside another. Reading and copying standard (楷書), semi-cursive (行書) and then cursive forms character after a character is considered one of the best and most proper ways of beginning and continuing studies of Chinese calligraphy.  Simplifying certain radicals in cursive hand carries dangers. Left-hand side radicals such as 言 (gen, i.e. “word”), 氵 (sanzui, i.e. “water radical”), and 冫 (ni sui, i.e. “ice radical”), can be written in the exact same way. Therefore, the only way of deciphering the meaning of the given text will be either studying the right-hand side of the character, or guessing it from the context, which by the way will be quite intuitive in cursive script. On the other hand, one radical can be written in various manners. If we take 言 as an example then it can appear in one of the forms shown in the picture (left). Chinese calligraphy in cursive script is, or ought to be, written without thinking or planning. Any pondering or hesitation will ruin the flow of precious energy. Thus, there is no time for deciding how to write given character. It happens automatically. And since some characters have repeating radicals, it is the calligrapher’s mastery level of the art that will determine how rich in various forms the text will be. None of the Chinese scripts is rule free. Cursive hand is no exception here. These are: 1. Merging strokes that are separated in standard form 2. Changing the starting point of a following stroke 3. Dots merged in one single line 4. Straight lines are represented by curved lines, sharp corners by loops 5. Reduction of total number of strokes 6. Long lines are shortened or symbolised by dots 7. Complex radicals are significantly simplified 8. There is a change in a positioning of given stroke 9. Stroke order is altered 10. Starting point of an initial stroke is changed This does not exhaust the subject of cursive script. Its another very characteristic feature is so called “unbroken line” (連綿体i). This technique is also essential in Japanese kana script, which was based on cursive forms of Chinese characters, or more precisely, manyōgana (万葉仮名, lit. "kana of ten thousand leaves [words]"). The “unbroken line” is the connection, be it visible or not, between the characters. In other words, an instance where two or more Chinese characters are literally or metaphysically combined into one flow. If a calligrapher was to stop after each Chinese character, and think how or where to write the next one, the flow would be broken. The secret of the rhythm and beauty of cursive hand lies in both well balanced forms of the characters, as well as the natural appearance of the composition, that allows the eye of the reader to glide with ease down the row of Chinese characters. “Unbroken line” seeks its way through a page of paper as a mountain creek searches for the shortest way to the sea. The undisturbed flow of energy (行氣) is the beating heart of cursive hand.  Cursive script is extremely intriguing. It is difficult to read, write and even to place its origin on a timeline (see this link to read my articles on the history of calligraphy and calligraphy scripts). Its definition is irregular and very flexible, just like its appearance. Even though it was, and still is in some cases, the most common script used daily by all the nations whose language is based on Chinese characters, not many of the modern native speakers can actually decipher it, let alone apply it with natural fluency in every day written communication. Modern civilization and computerisation of lives is to blame. It is no wonder, however, that the vast possibilities of expressing oneself are the reason for so many calligraphers to prefer to write in cursive hand. It is dynamic, abstract, passionate, favours subconscious creativity, and it is extremely expressive. Calligraphy written in cursive script may seem to be a maze of random brush strokes, or a late Picasso painting of anaconda snakes mating in their nest, but the paradoxical feature of it is that despite its random looks, cursive script requires a lot of precision and knowledge.  The studies of cursive script are long and taxing, starting with learning the basics of standard (楷書), semi-cursive (行書), and clerical scripts (隷書). Even though, historically speaking, cursive script preceded semi-cursive and standard scripts, it could be seen as an allegory for all three. The concept of cursive script is to emphasise the most characteristic features of the characters, and simplify them into a form that allows for faster and more fluent writing. However, those “shortcuts” are not any near being random, but rather carefully designed blueprints by some 2000 years of practical use. There are two major factors of cursive script that define its complexity. First one is that to writing in a way that brush is lifted from the paper surface as few times as possible (see my articles on the “unbroken line”). The second one is omitting and simplifying certain parts of a characters. As you may know, Chinese characters are built of radicals. Some characters may have completely different meaning, even if they share the same radicals (or radicals that look identically or nearly identically in modern standard script form). For instance 左 (hidari) means “left”, whereas 右 (migi) means “right”. The appearance of the 𠂇 (Japanese: sa, i.e. pictograph of a hand) seems to be nearly identical in both characters in the standard script, but its cursive forms will differ. This is because the etymology of the character 左 tells us that 𠂇 depicts the left hand, and in 右 it depicts the right hand. The stroke order of both differs in seal script (篆書), hence the difference in writing in cursive script. The stroke order of writing both characters in standards script also differs. Those may seem like small nuances, but such details have a massive impact on the composition and the flow of writng. Even in the case of a simple radical 口 (kuchi, i.e. “mouth”), the cursive forms might, or might not, have similar shapes. It all depends on the overall appearance of given character, or the calligraphy work composition. For example, it is possible that a cursive form of the Chinese character 口 in 右 may be written in a completely different way than that in 和 (wa, “harmony”), and usually it is so (see the diagram above). I invite you to view my tutorial on cursive script (videos included) |

Categories

All

AuthorPonte Ryuurui (品天龍涙) Archives

August 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed